North Rim Ranches

Restoring historically overgrazed lands north of the Grand Canyon

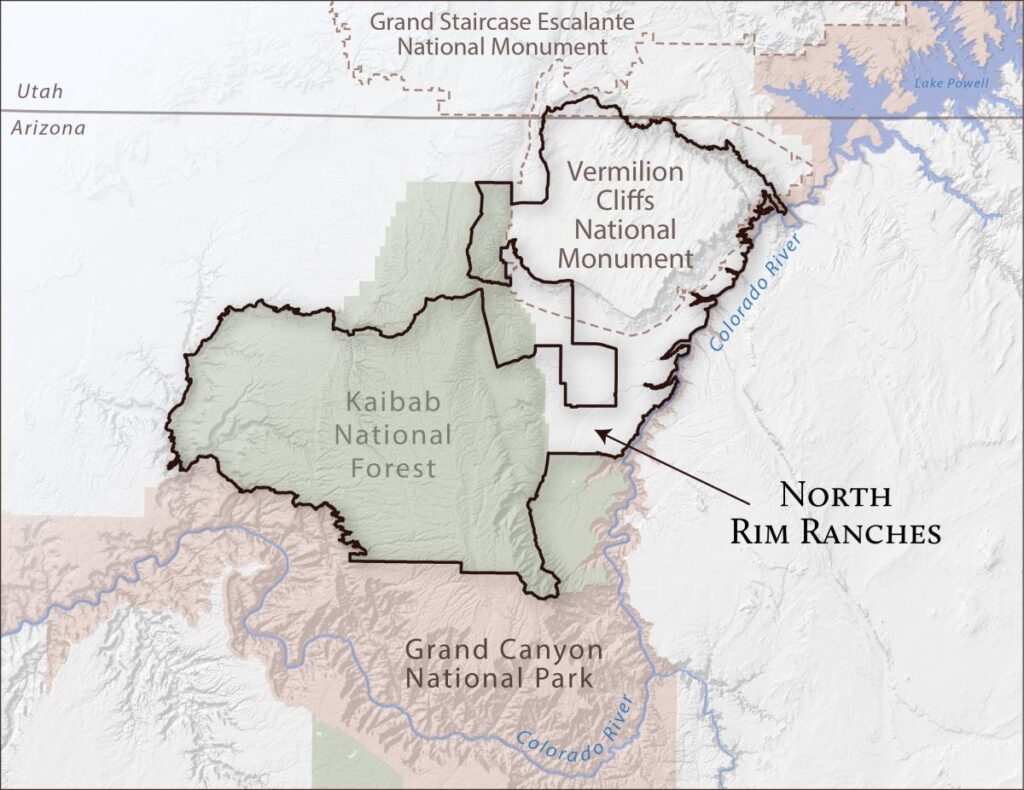

The North Rim Ranches stretch across 830,000 acres of public lands north of the Grand Canyon.

These are working ranch lands, where we run a small herd of cattle, as well as research and restoration grounds.

North Rim Ranches span across old-growth ponderosa forests in Kaibab National Forest, swirls of slickrock on the Paria Plateau, and arid grasslands in House Rock Valley. We partner with a ranching family, the U.S. Forest Service, U.S. Bureau of Land Management, scientists, volunteers, and others to learn what’s best for the land and translate science into action on the ground.

We strategically graze cattle

While our permits allow us to graze several thousand animals, we have reduced the herd to some 600 animals today to lessen the toll on the land. We also use grazing rotations that give grasses time to recover and reduce erosion.

We restore habitats

We are actively restoring wildlife habitat and waters across the North Rim Ranches. With the help of volunteers, we’re modifying fences for pronghorn, planting native willows around springs, and protecting meadows.

We partner on research

We work with scientists, universities, and agencies to study plants, animals, wildfire, climate change, and grazing techniques on the North Rim Ranches. Our goal is to take what we learn and use it to improve the health of the land.

Why is a conservation organization a grazing permittee?

As a grazing permittee, the Trust works to minimize the impacts of livestock grazing by using science and supporting conservation-based land management on the North Rim Ranches. We restore waters and native plants across historically overgrazed lands, partner with scientists to answer questions about what better grazing management looks like, and test ideas for public-private partnerships.

About North Rim Ranches

In 2005, the Grand Canyon Trust bought grazing permits for Kane and Two-Mile Ranches, now collectively called the North Rim Ranches. Our permits cover 830,000 acres of national forest and Bureau of Land Management lands, and we work with the Jones family to manage the day-to-day ranching operations.

During the late 1800s and early 1900s, thousands of animals — up to 33,000 cattle and 100,000 deer — roamed around the Kaibab Plateau and House Rock Valley, stripping them of grass and vegetation.

Today, the Jones’ herd is about 600 — half the number of cows our Forest Service permit allows, and a quarter of our Bureau of Land Management permit maximum. By having fewer cattle on the land and moving them to different pastures at different times of the year, we give the land the rest it needs.

Research and restoration

We work with partners ranging from Ph.D. candidates, to archaeologists, to high schoolers, to retired volunteers, on research and restoration projects across the North Rim Ranches. Our ongoing work includes:

We’ve also cosponsored mule deer habitat studies, bird and bat surveys, and studies on endangered cactus pollination throughout the years.

A cultural landscape

The North Rim Ranches have a long history of human use. Ancestral Puebloans hunted, gathered, and farmed on these lands, building check dams, irrigation ditches, stone walls, and dwellings.

Today, the Kaibab Paiute, Hopi, Navajo, San Juan Southern Paiute, Zuni, Havasupai, and other Native American tribes maintain deep cultural ties to the lands that make up the ranches. Read about our work with the Hopi Tribe and Forest Service to build fences around lakes on the north rim of the Grand Canyon.

It’s getting hotter

Scientists agree. The Colorado Plateau will get hotter and drier throughout the rest of the 21st century.

As drought intensifies, snowpack disappears, and temperatures rise, we will have to come to terms with climate change in the already dry Southwest. We developed a climate adaptation plan for the North Rim Ranches to help us better manage our resources and prioritize restoration projects.

Science-based management

When it comes to managing the North Rim Ranches, we use science to make decisions. We strive for sustainable livestock grazing, fire-safe forests, invasive species control, wildlife connectivity, and climate adaptation. We collaborate with a team of people from federal agencies, state agencies, and academic institutions to find the best solutions. If we don’t know the answer to a management question, we use science to find one.

Grazing blog

Grand Canyon Conservation Support the Trust and protect the Grand Canyon

Your donation funds on-the-ground conservation efforts and advocacy work.