Damming Big Canyon, near Grand Canyon, would harm the Little Colorado River. The Big Canyon Dam is a bad idea.

On Tuesday, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission accepted a new preliminary permit application from Phoenix-based Pumped Hydro Storage LLC to build four dams on and above a tributary to the Little Colorado River.

The company had previously submitted two separate applications for similar projects located on the Little Colorado River on Navajo Nation land mere miles above where the river flows into the Grand Canyon, merging with the Colorado River at the confluence.

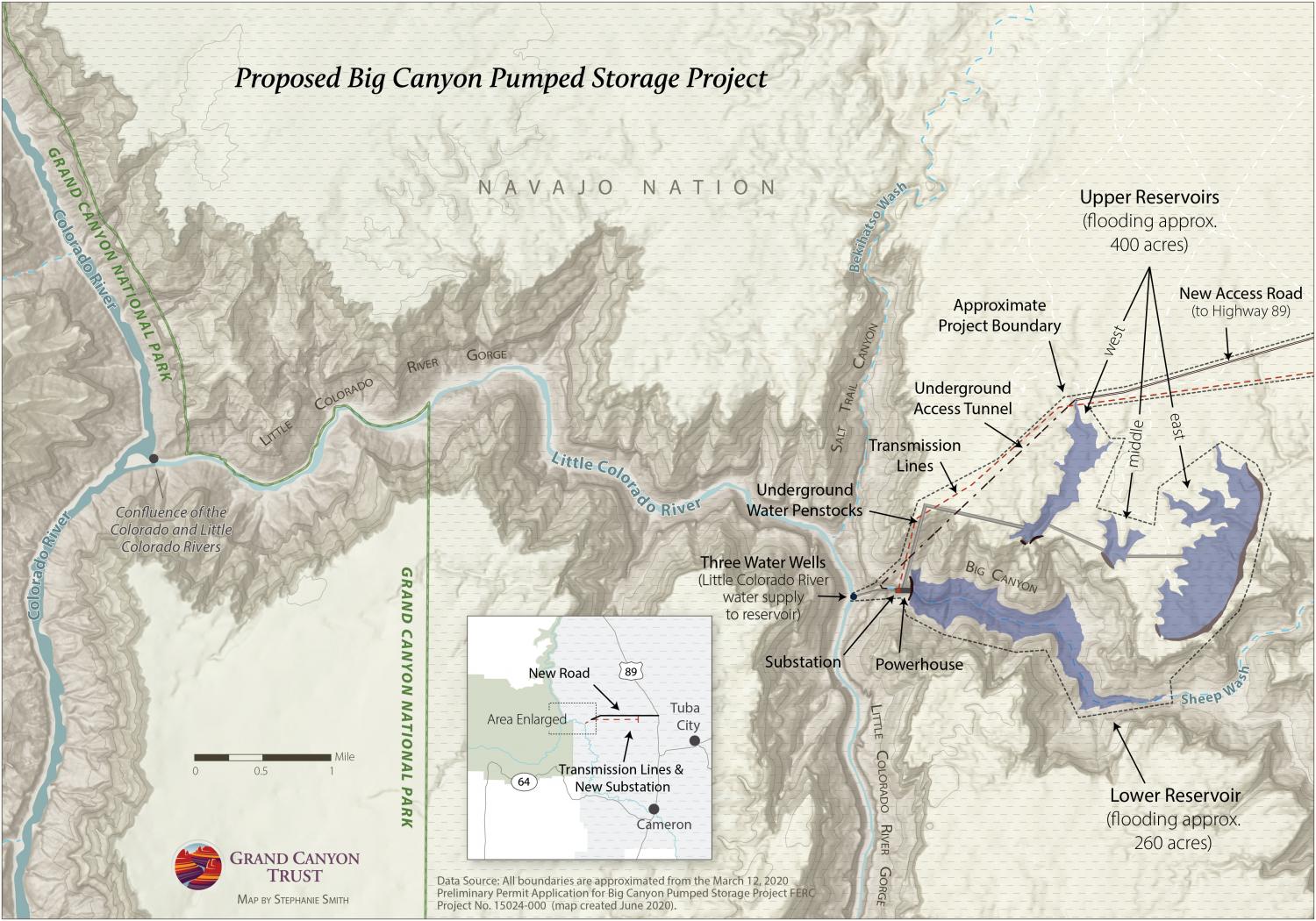

The latest proposal, also on Navajo Nation land, would pump groundwater to fill and refill the project’s reservoirs. Its lower dam would be built on the normally dry floor of Big Canyon, which joins the Little Colorado River near the site of another proposed set of dams.

A Pumped Hydro Storage LLC manager told the Arizona Republic: “We’re going to put a dam in there and drill wells and fill that up.”

Initial reactions to Big Canyon Dam proposal

“By disturbing this sacred area, they’re going to cause so much, not only pain to the Native Americans, but also to other civilizations out there,” Howard Dennis, a clan leader from the Hopi village of Mishongnovi, said of the proposals to dam the Little Colorado River. “I think it’s even going to be worse because when you’re sucking up groundwater, you’re taking it out from the springs,” Dennis said of the new proposal to dam Big Canyon.

Stanley Pollack, the attorney who filed the Navajo Nation’s motions to intervene in Pumped Hydro Storage LLC’s two earlier applications, said on social media: “This [new proposal] is still a problem because the Little Colorado River Gorge is protected by the Navajo Nation for its cultural and wildlife resources.”

Pollack added, “Moreover, the average salinity of the groundwater that feeds Blue Springs is about 2,500 ppm which may make pumping operations difficult.”

New proposal would replace two prior dam proposals

According to statements in the press, Pumped Hydro Storage LLC’s latest pitch would replace its two earlier Little Colorado River proposals with one project located on the Big Canyon tributary. The company seems to believe that this is a better plan than damming the Little Colorado River.

“Only one of these projects is going to go there,” the manager told the Arizona Daily Sun, indicating that the company would drop the two previous applications if this one is accepted. He added: “We tailored the new one to get it out of the Little Colorado to avoid all of the aquatic issues by putting the lower reservoirs in a dry canyon.”

How the Big Canyon project would work

The goal of the Big Canyon Pumped Hydro Storage Project, according to its developers, is basically to create a battery for electric-grid reliability. Water would be pumped from the project’s lower reservoir more than 1,500 feet uphill, when surplus electricity is being generated elsewhere on the grid. When energy demand changes, water would be flushed from three large storage reservoirs — built along the canyon’s limestone rim — and pass through 30-foot diameter pipes to where the hyper-pressurized water would spin blades on hefty generators bolted to the bedrock floor of Big Canyon.

The Big Canyon Project would have the capacity to store 3,600 megawatts of electricity — nearly three times the electricity produced by Glen Canyon Dam and 1.6 times that of Navajo Generating Station, which was the West’s largest coal-fired power plant before it closed in late 2019.

Consuming ancient groundwater

To generate electricity for sale across the western U.S., the massive power plant would consume groundwater, drawn from three wells drilled into the same aquifer that feeds the aquamarine springs scattered along the 13-mile reach of the Little Colorado River before it merges with the Colorado River in the Grand Canyon.

These aquifer-fed springs discharge billion gallons of water per year. It takes millennia for this ancient groundwater to emerge as springs along the Little Colorado River.

Wasting precious water

The investor-owned Big Canyon power plant would fill and refill its storage reservoirs every day to maximize electrical generation, sales, and profits. Its three wells would fill the lower reservoir with 44,000 acre feet, or about 14.3 billion gallons of water. From it, 9.4 billion gallons of water would then be pumped to the upper three storage reservoirs.

The developers guess that — to make up for evaporative losses — the wells would need to pump an additional 10,000 to 15,000 acre feet (3.2 to 4.8 billion gallons) per year.

But they fail to consider significant losses due to leakage from reservoirs built on fissured and faulted limestone. If well water is needed to replace lost water, the enterprise could end up consuming the equivalent of a significant portion of the Little Colorado River’s total annual flow.

Whatever the loss, it’s an unconscionable waste of water in a place where temperatures reach triple digits in the summer and locals count scant inches of precipitation per year as a blessing.

Turning a tin ear to tribes

Once again, Pumped Hydro Storage LLC is promising the Navajo Nation jobs and other benefits while dismissing the complex web of water, people, and aquatic communities that tie the Little Colorado River to the entire Grand Canyon.

“They have the real estate with the real wild topography. That’s what we need for pumped hydro,” the company told the Arizona Republic. “Anywhere we can get a big lift, take advantage of a big lift and a big drop, we can make a pumped hydro.”

Turning a tin ear to concerns raised by the Hopi Tribe and other tribal nations to earlier proposals, a company manager told the Arizona Republic: “Right now, I’m just concerned with the Navajo. It’s Navajo ground. It’s not Hualapai ground and it’s not Hopi ground.”

This focus flouts those whose sacred waters his business would pump for profit. Draining the Little Colorado River’s springs dry does not absolve the dam developers of “aquatic issues” that hobbled their previously problematic proposals. Reducing the Little Colorado River’s flow by any amount could harm already stressed aquatic life that relies on it for survival.

This latest application is deeply flawed as well.

Time to weigh in — again

The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC), which just recently greenlighted the company’s earlier applications, has opened a 60-day comment period for the preliminary permit application for the Big Canyon project.

Please tell FERC not to issue another permit for Pumped Hydro Storage LLC’s latest money-making scheme to exploit the Grand Canyon’s ancient waters at the expense of those who have made this place their home since time immemorial.

The deadline for public comment is August 3, 2020.