The first bucket of uranium ore may soon be lifted from Canyon Mine’s 1,400-foot shaft, stockpiled, and then trucked along the two-lane road that leads to Grand Canyon National Park’s busiest entrance. Its trail of radioactive dust will then blow along gateway town boulevards, where tourists enliven local economies, and through Native American communities—where last century’s uranium boom ended in a deadly bust.

Last month, the Arizona Department of Environmental Quality (ADEQ) re-issued Canyon Mine’s air pollution protection permit, as well as permits for Arizona 1 and EZ mines.

Public commenters had asked that, before the ADEQ re-approved the permits, it assess the cumulative effects of radon gas, radiation, and radioactive dust in the Grand Canyon region. The state’s air pollution permitting agency refused, stating “State law does not allow the Department to consider results of a study like this in a permitting decision for a specific site.”

The ADEQ will, however, allow for up to 26 million pounds of mined ore to be stockpiled to a height of 20 feet without a covering. The radioactive ore will be sprayed to control dust, and the runoff water must be contained in a plastic-lined pond so that it cannot leach into the aquifer that feeds springs deep within the Grand Canyon.

The permit also requires annual soil and quarterly gamma radiation sampling, the installation of anemometers, which measure wind speed, and a halt to truck-loading activities if wind speed gets above 25 mph. If dust or radiation monitors reach certain thresholds, the ore stockpile must be reduced by half, covered with a tarp, and protected by wind barriers.

The ADEQ responded to public concerns regarding tarps covering the radioactive ore on the 24 haul trucks per day—traveling at speeds up to 65 mph—by requiring that the tarp “be lapped over the sides of the haul truck bed at least 6 inches, and secured every 4 feet with a tie down rope.”

“We are very upset that ADEQ approved the air quality permits,” stated Havasupai council member Carletta Tilousi. “Even though we stood firm on protecting the lands and sacred areas, again the state of Arizona won’t protect our Grand Canyon homelands as they went ahead and issued the air quality permits. We are very disappointed with the agency.”

Grand Canyon’s Uncertain Future

In 1986, the U.S. Forest Service approved the development of Canyon Mine on public lands within a few miles of Grand Canyon National Park. When issuing the permit, it stated that “neither the water quality on the Havasupai Indian Reservation nor Grand Canyon National Park should be environmentally affected either directly or indirectly by the development of the Canyon Mine.”

Havasupai leaders appealed the decision but lost. However, due to a downturn in the uranium market, the mine shut in 1991 after sinking its shaft only 50 feet.

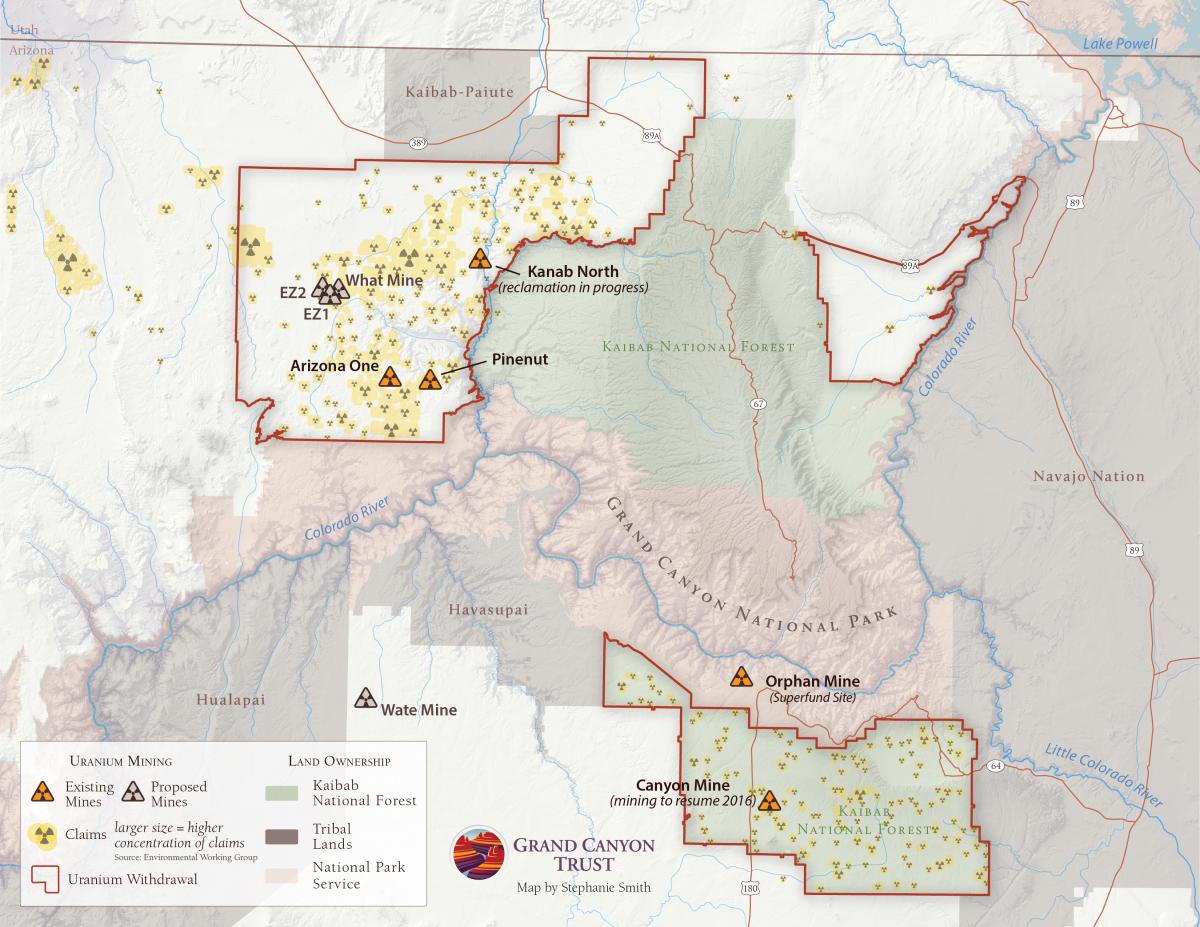

During the next two decades, water samples drawn from a spring below the nearby Orphan uranium mine confirmed that the now defunct mine is causing unsafe levels of dissolved uranium. The National Park Service now warns hikers against drinking from it. In 2010, water samples taken by the U.S. Geological Survey identified more contaminated sites “related to mining processes.” They found 15 springs and five wells that contained dissolved uranium concentrations in excess of the Environmental Protection Agency’s standards for safe drinking water.

An upsurge in uranium prices in 2007 brought new life back to uranium mines and a wave of new uranium claims.

Despite mounting evidence that uranium mines are polluting Grand Canyon’s fragile seeps and springs, the U.S. Forest Service allowed Canyon Mine to resume operations, without updating its 1986 plan of operations and environment impact statement as required by law. The Havasupai Tribe, the Grand Canyon Trust, and other plaintiffs’ 2013 lawsuit against the agency was denied in federal district court in 2015.

The Havasupai Tribe appealed the ruling to the Ninth Circuit Court. The Grand Canyon Trust, Center for Biological Diversity and Sierra Club soon followed suit. Oral argument in appeals regarding the Canyon Mine will be heard and streamed live at the Ninth Circuit Court in San Francisco on Thursday, December 15, 2016 at 9:30 am. Appeals regarding the mining industry’s lawsuit to overturn the 2012 mineral withdrawal—which put a 20-year ban on new uranium claims—will be heard immediately thereafter.

Depending on what the appellate court decides, Grand Canyon National Park will enter its centennial-year celebration in 2019 either as a place where citizens and common sense have prevailed, or as a prize under siege by mining interests.