Cutting national monuments won’t solve an imaginary national energy emergency.

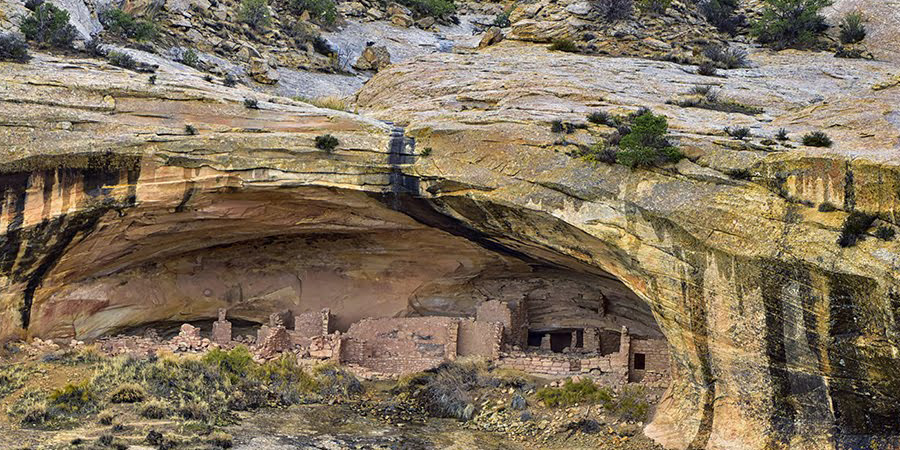

Grand Staircase-Escalante, Bears Ears, and Baaj Nwaavjo I’tah Kukveni national monuments are irreplaceable cultural landscapes. They showcase an unbroken record of human flourishing that stretches back at least 600 generations. They protect unmatched scenery and geology. Grand Staircase-Escalante in particular houses a remarkable trove of dinosaur fossils, many of which are new discoveries to Western science. All three monuments offer intact wildlife habitat to hundreds of species. And all three offer the emerging promise of Indigenous co-stewardship, where Native practitioners employ traditional knowledge to restore springs, medicinal plants, cultural practices, and more.

The new administration seems to think opening the monuments up to mining and drilling will solve an imaginary “national energy emergency.” It won’t. But rolling back monument protections will almost certainly lead to the destruction of natural and cultural heritage in places that are, simply, too precious to mine.

There is no national energy emergency

On January 20, 2025, President Trump declared a “national energy emergency.” Despite the United States being the world’s largest oil producer and having produced more crude oil than any other nation in history for at least six years in a row, Trump’s executive order tasks federal agencies with developing more energy production and infrastructure on public lands.

Interior’s national monument review

In response, on February 3, 2025, Secretary of the Interior Doug Burgum issued a secretarial order to make more public lands available for drilling and mining. Burgum’s order specifically targeted national monuments created under the Antiquities Act of 1906. And it set a February 18, 2025 deadline for agency staff to outline action plans to potentially cut or revise monuments. Never mind that cutting national monuments would be wildly unpopular with the public.

That February 18 deadline has come and gone. It’s unclear whether we will ever see Interior’s action plans. On March 7, 2025, a spokesperson for Secretary Burgum told the Los Angeles Times “[a]t this stage, we are assessing these reports to determine if any further action is warranted.”

Even if there was a national energy emergency, cutting Grand Staircase-Escalante, Bears Ears, and Baaj Nwaavjo I’tah Kukveni national monuments wouldn’t solve it. And opening up the monuments to mining could have devastating consequences for lands, waters, animals, and cultural places.

Very little energy potential within Bears Ears National Monument

At Bears Ears, when President Trump slashed the monument’s boundaries by 85% in 2017, even staunch monument opponents admitted the reduction didn’t have to do with the monument “locking up” vast energy resources. Gary Herbert, Utah’s governor at the time, wrote that, “[m]ineral resources beneath Bears Ears are scarce. There is no developable oil and gas. The region’s nonrenewable resources, including uranium near the Daneros Mine, were actually outside the expansive monument boundaries…”

Utah’s Department of Natural Resources backed this up. According to the department, “…as originally designated [Bears Ears National Monument] does not hold significant energy development potential. The vast majority of energy potential resides outside the monument boundary.”

However, this won’t stop mining enterprises, large and small, from trying if monument protections are removed. When President Trump slashed Bears Ears’ boundaries in 2017, the Easy Peasy uranium mine reopened on lands cut from the monument, scarring the landscape with heavy machinery and piles of radioactive waste rock.

Energy potential in Grand Staircase limited too

At Grand Staircase, the last exploratory oil well was drilled in 1997. It didn’t strike oil. In fact, Conoco walked away from all of its leases in the monument. Grand Staircase does contain large quantities of unmined coal. But after the monument’s creation in 1996, the federal government bought out 17 coal leases for $14 million.

Though Grand Staircase contains Utah’s largest undeveloped coal field, transporting that coal to market would have been extremely costly, and in the 21st century the regional market for it has dwindled. Multiple coal-fired power plants across the Four Corners region and around the country have been decommissioned as a part of a market-based transition to cleaner energy.

Utah has made millions by trading for energy-rich lands outside the monument

To offset potentially lost revenue, scattered square-mile parcels of land in Grand Staircase-Escalante owned by the state of Utah and managed by the Utah Trust Lands Administration were traded out of the monument by an act of Congress in 1998. As a part of the deal, Utah received a $50 million cash payment. The state has banked hundreds of millions of dollars in royalties from lands developed for energy that Utah acquired elsewhere in the state.

However, if Grand Staircase gets cut, we can expect miners and drillers to once again eye the monument, marring the landscape and threatening precious water sources.

Uranium in Baaj Nwaavjo I’tah Kukveni – small amounts, far apart

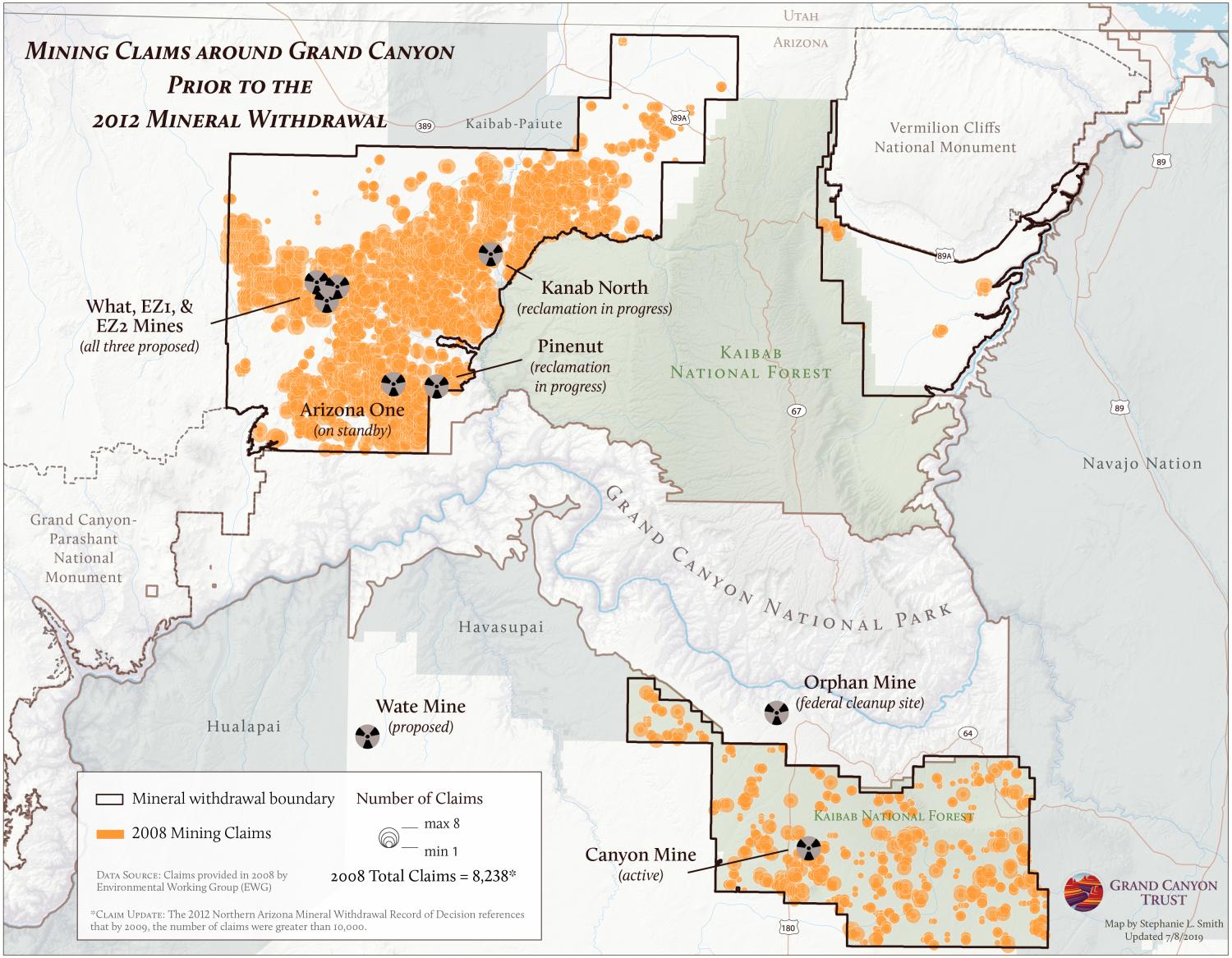

At Baaj Nwaavjo I’tah Kukveni – Ancestral Footprints of the Grand Canyon National Monument, uranium deposits are far flung and there isn’t very much of it. Only 1.3% of unmined uranium reserves and estimated additional resources in the U.S are within the monument. And you’d need many small mines to reach them. The entire U.S. only has 1% of global uranium resources and will never be uranium independent.

Nevertheless, uranium prospectors and multinational mining companies staked more than 10,000 mining claims around the Grand Canyon before all new mining operations in the area were banned in 2009. If that ban is undone, mining claims would inevitably surge again, and there would be nothing to stop a claim from becoming a mine.

And when you look at the risks posed by the single uranium mine currently operating inside the Baaj Nwaavjo I’tah Kukveni national monument — Pinyon Plain Mine (formerly Canyon Mine) — it’s clear just how devastating each mine can be.

What happens next?

Will Grand Staircase-Escalante, Bears Ears, and Baaj Nwaavjo I’tah Kukveni national monuments be sacrificed to an imaginary national energy emergency? We don’t know. Late at night on March 14, 2025, a fact sheet appeared on the White House website. It said that President Trump had “[t]erminat[ed] proclamations declaring nearly a million acres constitute new national monument.” But no such order was posted. By the next day, the reference to monuments in the fact sheet had been scrubbed.

Come what may, we are prepared to respond to any executive action threatening our beloved national monuments. These monuments are too precious to mine. We will do all that we can in the courts, in the halls of Congress, and on the ground to preserve them as we have before. And we’ll continue counting on you to raise your voice in their defense.

Protect Bears Ears and Grand Staircase

On February 12, 2025, U.S. Secretary of the Interior Doug Burgum said he would not target national parks and monuments for energy development. Urge him to keep his promise.