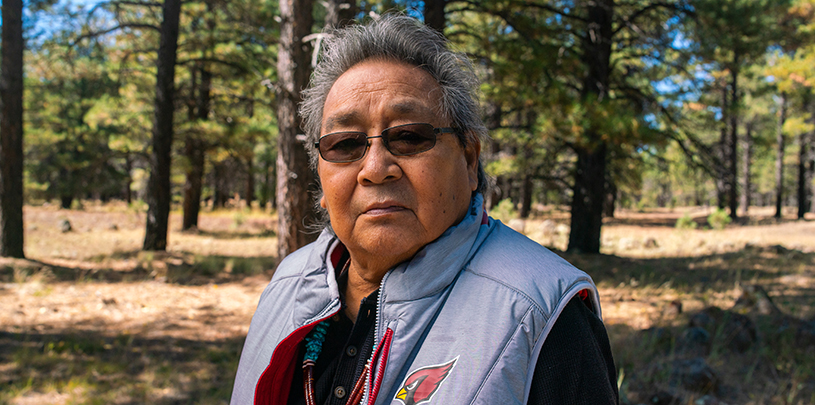

Hear from Leigh Kuwanwiswma about his Hopi cultural connections to the Grand Canyon.

Growing up in the Hopi village of Bacavi on Third Mesa, Leigh Kuwanwisiwma helped plant his family’s cornfields each spring. His grandpa would give him a handful of seeds along with careful instructions: “When you get to the end of the row, take a look back.” As a young boy, Kuwanwisiwma followed the teachings of the over-the-shoulder glance to make sure the corn rows were straight and spaced far enough apart for a tractor. But in adulthood, his dad clued him in to the deeper lesson in his grandpa’s words. Kuwanwisiwma says what his grandpa meant is that you never know where you’re going unless you know where you came from.

For Kuwanwisiwma, there’s no question about where he comes from — his people’s handprints are painted on cliff walls, his clan symbols etched in rock, and his heart and spirit tied to Hopi land. Here, we talk with Kuwanwisiwma, the former director of the Hopi Cultural Preservation Office about his cultural connections to the Grand Canyon.

READ, LISTEN, WATCH, AND LEARN: Find more cultural stories in The Voices of Grand Canyon

What is your Hopi connection to the Grand Canyon?

The Grand Canyon is very special to us. It’s our genesis, and it’s also our final spiritual home. The Hopi are taught that we traveled through four stages of life, which are still remembered vividly in our rituals, through songs, and clan traditions. And finally we emerged here, into the 4th world. The Hopi say we emerged from the Grand Canyon at a place called Sipapuni, which is the path to the underworld. From there on we were told to migrate, and put forth our footprints as far as we could. So the evidence we have now in terms of the migrations, are all of the ancient ruins out there that Hopi still connect to.

What’s the significance of the confluence of the Colorado and Little Colorado Rivers in the Grand Canyon?

Eventually we will travel into the spiritual world. When that happens, a spirit travels to the Grand Canyon, particularly around the area of the confluence, which is home for our ancestral people and the spirits. And from the Grand Canyon, the spirits travel throughout the world as clouds. So every day, they are with us. When we see clouds, we are told to revere them by not directly looking at them, because they are the spirits of our ancestors. This is a very special place for us, right there at the confluence. We continue to have tranquility, silence, because our spiritual people need that as well.

Where do the Hopi live today?

We’re located approximately two hours south of the Grand Canyon, about an hour and a half from the San Francisco Peaks. We’ve been here for about 1,000 years in our present Hopi villages. But beyond that you still have the history of the Southwest and you have thousands and thousands of ruins that the Hopi consider their footprints — evidence that the Hopi clans traveled through there, and eventually returned or came back to the spiritual center, which are the Hopi mesas. So today, the Hopis still remember through their traditions and clan histories, their migration routes. And within those migration routes, is a living connection to these sites that are not abandoned as archaeologists say, but still living. Our villages are still living entities to the Hopi people.

How do you maintain your cultural connections to the Grand Canyon?

What I try to do in my family is talk about our clan history — which is the Greasewood Clan. I guess I’m the teacher for them. And we’re doing the same thing in our kiva groups too, where we have younger people down there. So we do the Kachina teachings — the essence of the Kachina beliefway. I think the culture is able to survive in terms of its connection and understanding of who we are. And I hope it survives.

Do you have any tips for tourists visiting the Grand Canyon?

For visitors coming to the Grand Canyon, particularly for the first time, you see how monumental it is. The expanse of the canyon, the way it affects you. You just get swallowed by the canyon. And I think it just challenges yourself, like gosh, how could this be. How could this be part of our life? It’s gorgeous and so huge, and all of the animals — bighorn sheep, deer, cougars, wild burros — down there. I think when people go there, they need to take a big breath and look out over the Grand Canyon, and also honor it. Because for the tribes around here, including the Hopi, it is very special to us. I think it’s really an honor to be able to go and visit the canyon.

Hear more from Leigh and learn about other cultural connections to the Grand Canyon in The Voices of Grand Canyon