Last month’s announcement that one of the nation’s largest coal plants would soon close caught many people by surprise, especially those who have the most to lose.

Hundreds of power plant and coal mine workers had hoped they could hang on to their well-paid jobs for at least another decade.

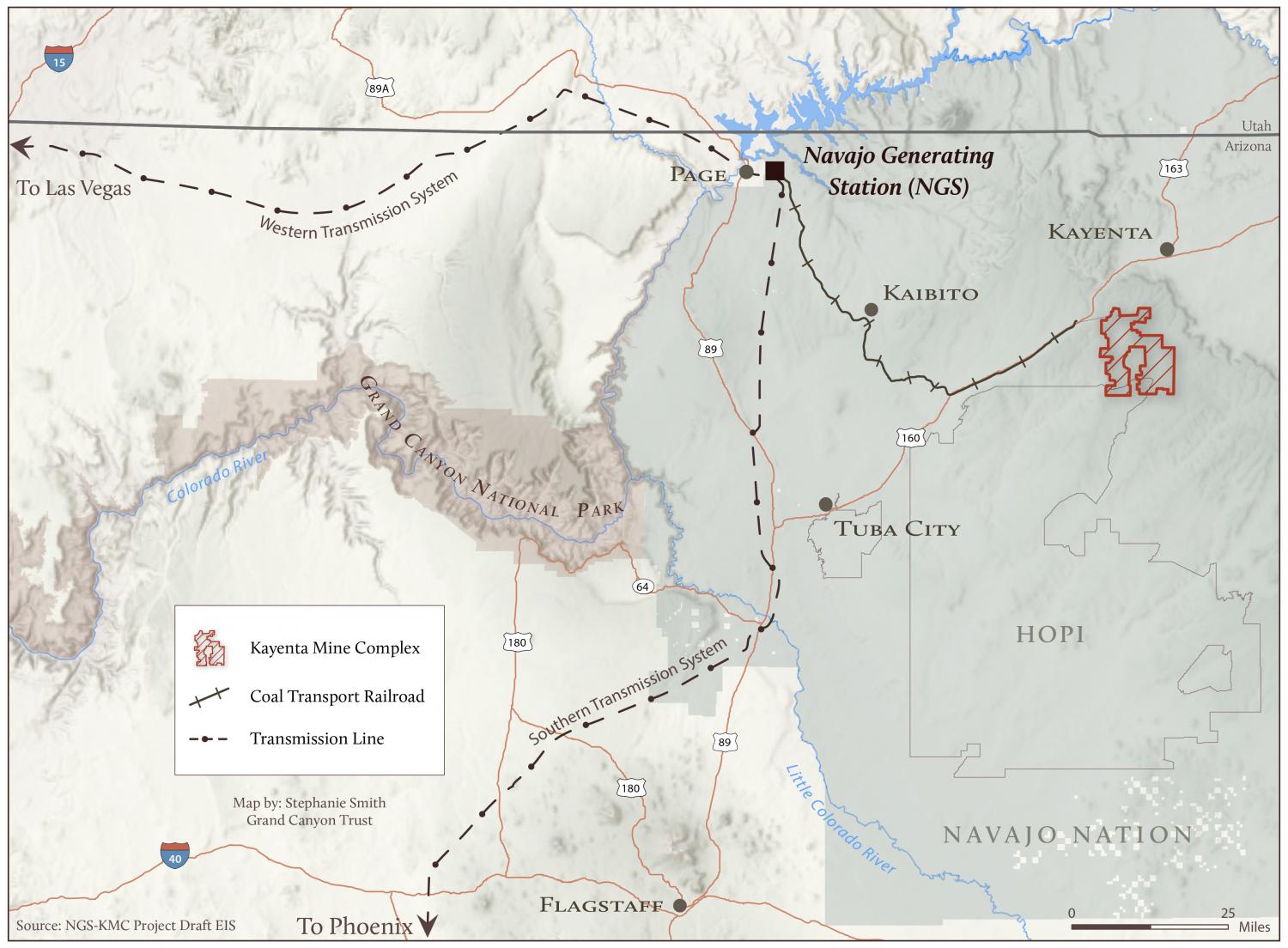

For 43 years, Navajo Generating Station (NGS) has been burning coal that is strip-mined from Hopi and Navajo homelands. It has provided good jobs, funded tribal governments through lease payments and royalties, and supported college scholarships for local students.

The low-cost electricity from the power plant also pumps water uphill, from the Colorado River to Phoenix and Tucson, via the Central Arizona Project. Burning as many as 1,000 tons of coal an hour for more than four decades, the plant has dumped hundreds of millions of tons of climate-altering gasses and biological toxins onto the land, air, and water since Navajo Generating Station started generating electricity and sending profits to shareholders.

In late 2016, the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation released a comprehensive Draft Environmental Impact Statement. It concluded that to provide the cheapest water to Central Arizona Project customers, the best path forward was to keep Navajo Generating Station running through 2044. Navajo and Hopi leaders had previously negotiated new royalty rates for the coal that powers the plant. The Navajo Nation had renegotiated land leases for the coal train, power plant, and transmission lines. All necessary permits were falling into place to keep business running as usual. Or, so they thought.

Utilities decide to close NGS

On February 13, 2017, Salt River Project, Arizona Public Service, Tucson Electric Power, and Nevada Power decided to close NGS by the end of 2019, or possibly sooner. They said that the cost to purchase and burn coal to make electricity was too high to keep the coal plant running.

“The utility owners do not make this decision lightly,” said a Salt River Project spokesman, acknowledging that electricity generated by NGS is why “the state of Arizona and the Phoenix metropolitan area have been able to grow and thrive.” But Salt River Project concluded that “the higher cost of operating NGS” is not something its million plus customers should bear.

Salt River Project, the majority owner and operator, said that it would consider keeping Navajo Generating Station running up until the lease ends on December 22, 2019. But the Navajo Nation would need to renew it beyond 2019 to allow time to “decommission” (disassemble, remove, and decontaminate) NGS. Salt River Project has set July 1, 2017 as the deadline for renewing the lease, or it will shut down NGS and start demolition this year.

Closing costs to Hopi and Navajo people

Navajo Nation Council Speaker LoRenzo Bates and Hopi Tribal Chairman Herman Honanie shared concerns about the economic impact of closing Navajo Generating Station and the coal mine that supplies it. Bates said, “SRP [Salt River Project] needs to take into full consideration the impact that a possible closure would have on the economy, jobs, and communities that rely on NGS.”

“The Hopi people are dissatisfied with the lack of transparency from SRP in its recent threats to discontinue NGS,” Honanie added. NGS-related revenues provide more than 80 percent of the Hopi Tribe’s general budget.

“We fully understand the economic and environmental issues that surround the plant,” said Navajo Nation President Russell Begaye. “We also know that NGS infuses $18 billion into the entire economy of Arizona.” Begaye has also said that closing NGS threatens economic security, stating that “Many people depend on this industry.” Keeping Navajo Generating Station running is now a “matter of national security” according to Begaye.

Focus on clean energy and water

Percy Deal, who lives near Black Mesa and represents Diné CARE, and other community leaders are welcoming the planned closure as “an opportunity to fix the many mistakes of the past and open the door for a more prosperous future.” Diné CARE works with Navajo communities affected by energy and environmental issues. Former Hopi Tribal Chairman Vernon Masayesva said, “I am very happy and relieved that Black Mesa Trust’s struggle to save sacred waters on Black Mesa will finally end in 2019.” Masayesva founded Black Mesa Trust to challenge the use of groundwater to strip-mine and slurry coal from Black Mesa.

Black Mesa Water Coalition’s Executive Director Jihan Gearon said she hopes the tribes can develop renewable energy projects to help replace revenues and jobs that will be lost. The grassroots organization has long advocated for a just transition away from coal to clean energy.

“Economic studies show how the transition can happen,” she said. “We sell energy to major Southwest cities. We can sell a more sustainable form of energy, using the many lands that are unfortunately already toxic and need to be remediated.” She added that the tribes should have an ownership in such developments, “So we are not just leasing land to another big company that receives all the profits.”

Another advantage of the plant’s closure, according to Percy Deal, is that the water it has been pumping from Lake Powell could be made available as drinking water in Native communities where it’s sorely needed. “It’s clean water that they’re using,” he said. “I really believe that it’s time to put an end to that. That 31,000 acre-feet of water is Navajo water, and for almost 50 years now, Navajos have not been able to use it.”

Hopi and Navajo advocates agree that it’s time to move away from coal and to focus on more sustainable alternatives that would benefit the environment as well as the economic health of Native people living near the plant and coal mine.

Next steps

Reports from last week’s meeting between the Bureau of Reclamation and the tribes, utilities, Central Arizona Project, and other stakeholders indicate that working groups have been tasked with negotiating a new lease agreement before the July 1 deadline, identifying an economical pathway to keeping NGS operating as a coal plant beyond 2019, and creating alternatives for mitigating impacts in the event NGS closes, possibly as soon as this year. They plan to reconvene in mid-April. Reclamation has also indicated its intent to meet with community leaders and indigenous grassroots groups.

Arizona Corporation Commissioner Andy Tobin commented, “I think the positive I took away from the meeting is that there was a large crowd of stakeholders who appeared to be hungry to keep NGS, as an institution, operational. SRP is not in that group.” Although Salt River Project has ruled out plans to participate in the plant beyond 2019, it has said that it is willing to work with tribes on renewable energy projects and on securing transmission and water rights.

We are still living in an era where economic and environmental costs are borne — asymmetrically — by Native people. The system is structured such that the bulk of the benefits flow to distant centers of prosperity, while the land and people who produce the profits pick up the tab. When it becomes more profitable to buy electricity elsewhere, utilities give priority to their customers, leaving Native communities to carry the closing costs into future generations.

Several consequential outcomes are emerging as Navajo Generating Station approaches its inevitable retirement. The Grand Canyon Trust supports community-based solutions linked to sustainability, clean air and water, and tribal equity. We join others in wanting to rewrite the ending to the same old story about another boom that’s gone bust, when the closing curtain falls on Navajo Generating Station’s final act.