A Canadian company intends to begin mining inside the original boundaries of Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument this summer.

We’re dealing with prolonged drought and sweltering heat this summer on the Colorado Plateau — these are predictable, and troublingly, more and more common. Predictable as well are the wildfires in Utah, Colorado, and New Mexico that the drought, heat, and wind bring us. But where these fires start can be unpredictable.

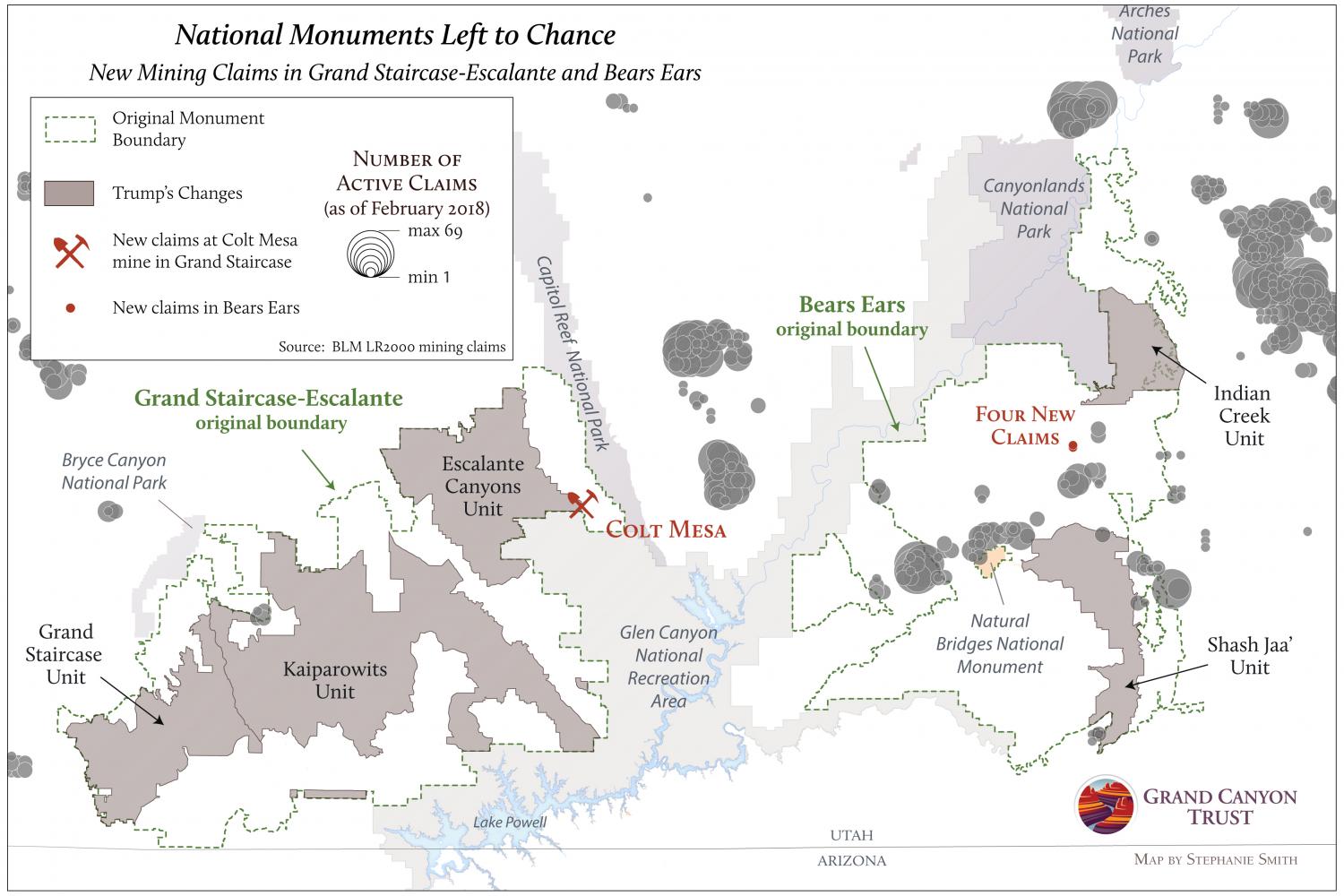

The same goes for new mining claims in the lands President Trump attempted to ax from Grand Staircase-Escalante and Bears Ears national monuments last December. Like wildfire, they are expected and can be destructive, but where they will pop up is somewhat of a mystery.

Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument faces mining risks

Four new mining claims have been filed in Bears Ears by private individuals from Texas, but without financial backers, their endeavor does not seem serious. The real concern now is over in the Circle Cliffs region of Grand Staircase.

On June 13, 2018, a Canadian company, Glacier Lake Resources, announced that they’d acquired copper and cobalt mining claims at Colt Mesa, inside the original boundaries of Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument.

The company’s press release detailing the acquisition is loaded with cheerful optimism, and the company’s web page on the project states benignly that: “The Colt Mesa mine area was sterilized from exploration and development in 1996, when President Clinton created the ‘Grand Staircase Escalante National Monument,’ However, the size was recently reduced by Presidential proclamation in December 2017, which put Colt Mesa outside the new boundaries of the restructured national monument.”

Not so fast

The release claims that “[s]urface exploration work will start this summer on the Colt Mesa property and drill permitting will be initiated shortly.” Not so fast. These lands are the subject of several lawsuits asserting that President Trump acted unlawfully in attempting to gut Grand Staircase. And because that action was unlawful and void from the get-go, any mining claims staked in the area removed from the monument are void too.

The company may have struck a public relations disaster and exposed its investors to dangerous uncertainty before it has even turned a spade of dirt.

Glacier Lake may have even bigger problems than public relations. According to a research paper, the mine was worked only intermittently from 1971 to 1974. What brought an end to mining and led to the abandonment of the claim? Lack of available water. Water doesn’t suddenly appear with time in the desert. Also lacking at the mine site are heavy-duty haul roads, electricity, and access to rail lines.

The nearest town — Boulder, Utah — is doing quite well with agriculture and tourism, and it’s not about to reimagine itself as a mining service community. In fact, many residents are upset at the prospect of a new mine in Grand Staircase. They live in Boulder because it is minutes from some of the wildest country left in America.

But here’s the kicker: The Colt Mesa property is located on lands that were purchased by U.S. taxpayers as a part of a larger congressional land exchange for Grand Staircase in 1998. That’s right — we spent $50 million from the U.S. Treasury to ensure that this and other parcels would be transferred from the state of Utah to Bureau of Land Management ownership to be permanently protected — not mined.

What does the possibility of new mines in Utah’s monuments do to you? Are you angry? You should be. Hopeless and despondent? Not for a minute. Galvanized to defend our irreplaceable national monuments? Now you’re talking.

Send a note to the Bureau of Land Management

Staking a mining claim does not amount to an automatic license to mine. After staking a claim, a mining company must, at the very least, notify the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) of its mining plans and give the BLM a chance to demand more safeguards for our public lands. And the BLM must sign off on plans to mine more than five acres. We’ll let you know if that process gets underway for Colt Mesa.

In the meantime, you can email the BLM at blm_ut_so_public_room@blm.gov and let the agency know that you love your public lands and oppose mining at Colt Mesa and anywhere else in the original Grand Staircase-Escalante and Bears Ears national monument boundaries.