Scientists are learning more about the wildly complicated ways water moves through the Grand Canyon, and how what happens above ground affects what flows beneath.

It’s dead summer, and the Grand Canyon simmers in hot, heavy air. Even the most heat-adapted creatures are in refuge. But today is a special day. Emerging from the shadowy depths of a cracked boulder, a collared lizard pokes its head out to lick the air — something’s afoot.

Just beyond the North Rim, over the Kaibab Plateau, rises a churning colossus of vapor and energy. Its dark, anvil-shaped crown stretches miles into the upper atmosphere, a 45,000-foot-tall billowing plume of rapidly cooled air hoisted from the canyon, raking the heavens. It’s the onset of monsoon season, an annual weather pattern that synchronizes and sustains life here — and this cloud is about to reach its tipping point and unleash untold volumes of water onto the land.

A vast and complex aquifer

With its elevated topography, the Kaibab Plateau grabs hold of moisture streaming inland from the Sea of Cortez like a catcher’s mitt. When the first veils of rain fall from the cloud’s swollen belly, there is little time to rejoice before a full-on deluge ensues. Flash floods thunder down the plateau’s flanks to the Colorado River.

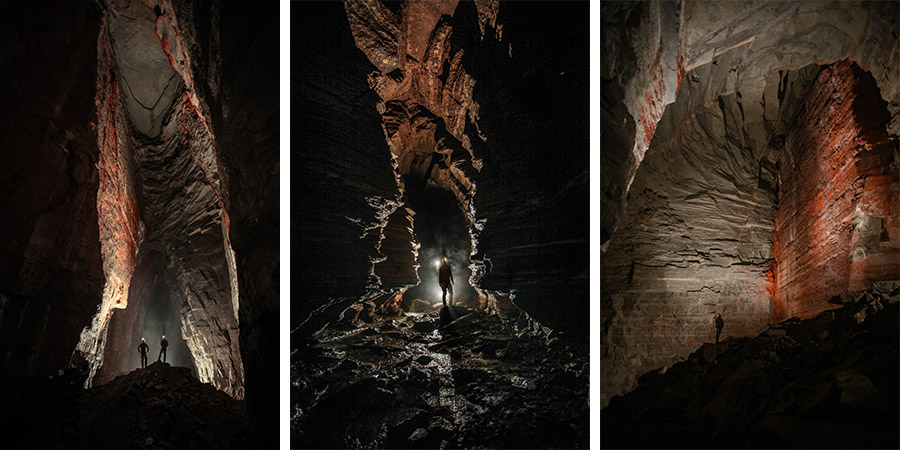

The water that doesn’t immediately roar into the canyons, instead, is funneled underground through sinkholes perforating the plateau’s forested exterior — inlets to a vast and complex karst aquifer, a natural wonder in and of itself, hidden inside the Kaibab. Hidden that is, until this same water reemerges in the Grand Canyon at one of the countless seeps or cave-held springs that gush into the open air dozens of miles from, and thousands of vertical feet below, where the water first entered the ground.

The Redwall-Muav Aquifer, as it is known, is perhaps the most important source of fresh water in the Grand Canyon, allowing for life to flourish with abundance in an otherwise arid climate.

But it’s more than just an underground reservoir. The aquifer is a source of spiritual and cultural significance for the Indigenous communities inextricably linked to its waters — a place of genesis and origin. And for the Western scientists and cave specialists who are working to unravel its secrets, and plumb its hidden depths, a rare picture is being painted of a vast and ancient aquifer system incised by the Colorado River — a system so complex that, for decades, it has puzzled and surprised, if not bewitched, those studying it.

How old is groundwater in the Grand Canyon?

Two days after the big rain event drenches the Kaibab, Garrison Loope, cave and climate specialist at Grand Canyon National Park, observes a significant increase in the flow rate and volume of water surging from the mouth of Roaring Springs Cave. This spring is a particularly relevant focal point as it is the park’s sole source of water.

Loope and his assistant huddle inside its large entrance chamber. Ambient daylight gently scatters along the walls, and cool, humid air flows like the water from deep underground — a welcome reprieve from the summer heat. The data they collect will help inform water management strategies and shed light on the subterranean mechanisms of the Kaibab’s flows.

Up-close monitoring keeps tabs on the aquifer and provides insight to the big questions: How long does it take for water to move through the system? What are its main flow paths? How does flow time vary from season to season? How old is this water? And, how vulnerable is the system to the impacts of a warming climate and other human-related activities such as mining?

Though its true mechanisms may seem impossible to track, in the last decade much has been learned about how water flows through the Kaibab’s manifolds, largely due to foundational research conducted by Dr. Ben Tobin, former Grand Canyon National Park hydrologist and cave resource specialist. Throughout the Colorado River Basin, a place where regional water supplies are strained and every drop is accounted for, such a poorly understood watershed is a pressing matter.

“We sure could stand to know a lot more about this water, especially if we’re putting all of our eggs in one basket with Roaring Springs,” Tobin says.

Loope’s work in the park monitoring springs is a continuation of an ambitious project initiated by Tobin in 2014 to trace water from high on the Kaibab Plateau all the way to Roaring Springs. How? A simple technique called a dye trace.

How far and how fast does Grand Canyon water travel?

When Tobin and his team of assistants zeroed in on sinkholes funneling runoff from snowmelt underground, they injected the water in question with an inert neon dye. To their surprise, it reached Roaring Springs in just a few days — after flowing a mindboggling straight-line distance of 23 miles and descending over 6,000 feet vertically — the deepest successful dye trace ever completed in the United States — revealing just how quickly water moves through the system.

Adding to the research team’s bewilderment, dye from two separate tests crossed underground, and emerged at two different springs, in two different canyons, but did not mix.

In 2021, Loope picked up where Tobin left off in the effort to trace water through the system. Of course, he anticipated surprising results.

“Before I dove into this project, I heard firsthand from Tobin about how he was constantly amazed that they would inject dye into a single sinkhole, and it would be detectable in multiple springs located significant distances apart. Dye at Roaring Springs would reliably get there [from the Kaibab Plateau] in a few days, while springs right next door had nothing,” Loope says. “If we have confirmed anything about what goes on inside the Kaibab, it is that it’s a wildly complicated system.”

“We had dye coming out all over the place”

Chuckling, Loope reflects on the past four years: “Our whole team is still struggling to interpret our latest data set.” Loope says that the biggest surprise so far this season occurred when they injected dye into one of the same sinkholes as Dr. Tobin had, with remarkably different results.

“We had dye coming out all over the place — everywhere except the spring Tobin had previously recorded. We’re still interpreting what this exactly means,” Loope continues, “But I surmise that the water table in the aquifer varies quite a bit from year to year and even throughout a single season. When the water table is higher, new possible flow paths are likely utilized by the water, and when the water table is low, it flows out of physically lower places within the aquifer.”

This fresh recharge isn’t the only water present in the system. Primordial water upwells from unimaginable depths through faults and rifts, providing ballast and balance for new water flowing into the system — a confluence of the inner Earth and the upper atmosphere.

The Colorado River has 10-20% more volume as it leaves the Grand Canyon

A challenge of managing underground resources is that they tend to fall into the out-of-sight, out-of-mind category. But one need not probe far to get a basic sense for the collective amount of water draining from the Redwall-Muav Aquifer. Removing the data from snow runoff, monsoon spikes, and dam releases, the Colorado River has 10-20% more volume as it leaves the Grand Canyon — a statistic that can only be attributed to the springs flowing from the aquifer.

Among the most well-acquainted with the Redwall-Muav Aquifer is the Havasupai Tribe, a name which translates to “People of the Blue-Green Water.” Havasupai people reside in the lush and vibrant Havasu Canyon below the Grand Canyon’s south rim, a community accessible only by foot, horseback, or helicopter. Carved by the life-giving waters of Havasu Creek, the canyon is a world apart, sheltering groves of cottonwood, willow, and mesquite, while cool, travertine-rich waters thunder over the iconic Havasu, Mooney, and Beaver falls.

Beyond the walls of Havasu Canyon, the ancestral lands of the Havasupai traditionally extend into the forested valleys and canyon rims that lead to their sacred mountain, Red Butte, near where the Pinyon Plain Mine, formerly Canyon Mine, is currently extracting uranium ore perched above the precious Redwall-Muav Aquifer.

Humming away in an otherwise tranquil meadow not far from the foot of Red Butte, the mine operates in the Kaibab National Forest, within the boundaries of the recently established Baaj Nwaavjo I’tah Kukveni – Ancestral Footprints of the Grand Canyon National Monument — specifically designated to protect ancestral homelands, including places of ceremony, life-sustaining water sources, hunting grounds, and other locations that figure prominently in Indigenous history. Despite the monument protections now in place, the mine continues to operate based on an outdated environmental impact statement (EIS) and the Havasupai Tribe fears the mine will contaminate groundwater.

In a 2024 letter to Nicole Branton, the Kaibab National Forest supervisor, Arizona Attorney General Kris Mayes stated that, “A supplemental EIS is now necessary because scientific advances in groundwater modeling unequivocally show that the 1986 EIS’s claim that the Mine is not a threat to regional water supplies is wrong. Failure to supplement the EIS could result in devastating consequences for the region — especially for vulnerable communities like the Havasupai Tribe.”

“In our Canyon home, water is life”

Although opposition from the Havasupai Tribe, and countless others, has been fierce, the operation continues to extract ore with risk of permanent contamination that will remain long after the mine closes — a toxic slurry of uranium ore and water, left to stew in a sealed shaft. What is the probability that this contaminated water will percolate into the Redwall-Muav Aquifer through faults and fractures that undoubtedly exist? Time will tell.

During testimony before the United States Senate, Havasupai Tribe Chairman Thomas Siyuja Sr. had this to say:

“In our Canyon home, water is life. This water travels deep underground, through layers of rock, across many miles, before it emerges to reach us. This is something our elders understood and taught us to respect, long before scientists confirmed what we already knew. The springs that flow from the rock walls are sacred and must be protected. Uranium mining on the Canyon’s rims, on our aboriginal lands, threatens to contaminate the aquifer that feeds Havasu Creek. We know the irreparable damage uranium mining can do. For generations we have been at the forefront, working to permanently protect our homelands from uranium mining, which has disproportionately harmed and sickened Indigenous people across northern Arizona.”

Thanks to the tireless work of researchers like Dr. Ben Tobin and Garrison Loope, as well as many others, a clearer — if still astonishingly complex — picture is beginning to emerge. Their dye-tracing studies have revealed just how quickly and unpredictably water can move through this subterranean network, linking seemingly unrelated sinkholes and springs across vast distances and vertical drops. Yet the more we learn, the more questions arise: How stable is this system in a changing climate? How resilient is it to human activities like mining? How long can we rely on Roaring Springs as a single point of supply in a park that hosts millions of visitors each year?

Putting Earth’s most valuable resource — fresh water — at risk

This fragile and dynamic aquifer doesn’t exist in isolation. It is part of a broader hydrological tapestry that stretches across the Grand Canyon region, feeding into the Colorado River and supporting ecosystems, Indigenous communities, and downstream users who may never see the canyon’s depths — but rely on its waters every day.

The controversial uranium mining operation on the ancestral homelands of the Havasupai people is a stark reminder that what happens above ground can irrevocably alter what flows below, putting what is arguably Earth’s most valuable resource — fresh water — at risk.

Ultimately, the Kaibab Plateau and the Redwall-Muav Aquifer are so much more than just a scientific puzzle or a source of water — they are a living system without boundary, physically connecting the deep earth with the upper atmosphere, weaving a thread through humanity, time, and space.

Stephen Eginoire is a photojournalist, writer, and designer based in southwest Colorado. Find more of his work at stepheneginoire.com

This story originally appeared in the fall 2025 issue of the Grand Canyon Trust’s Advocate Magazine.