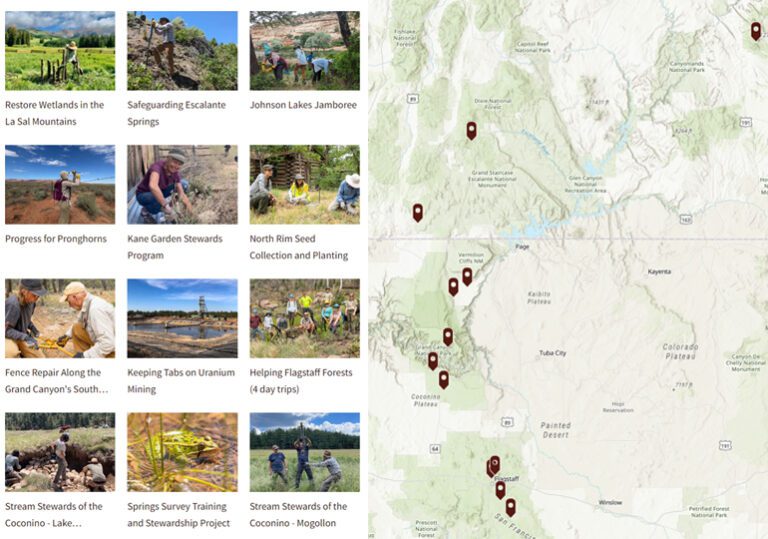

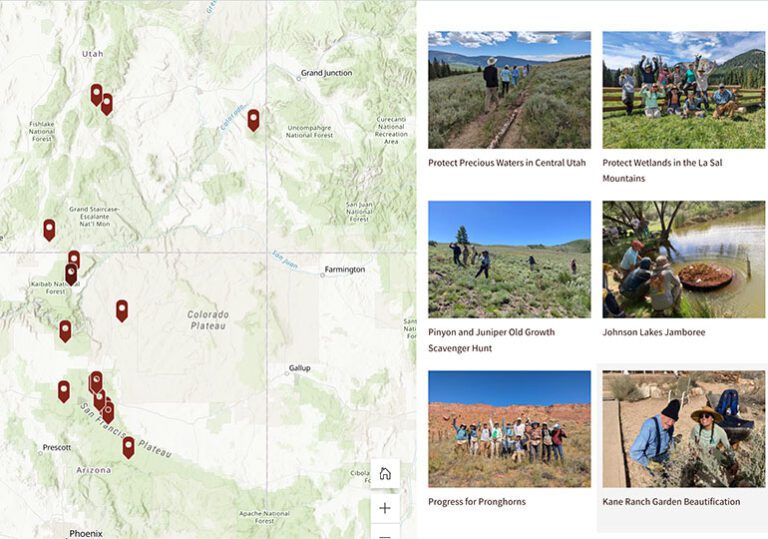

Volunteer Projects

From counting native grasses, to modifying fences for pronghorn, our volunteer projects connect people to landscapes while getting much needed work done.

We’re not afraid to get our hands dirty.

The tools we use vary between clipboards, data sheets, shovels, and iPads. Our volunteers put their hearts (and backs) into improving the health of public lands across the Colorado Plateau, dedicating their most precious resource — their time — to volunteer projects that make a difference.

Whether you have one day or a week to spend with us in the field, you can help protect wildlife habitat, water sources, and native species on the Colorado Plateau by joining a volunteer project. Travel with us to some of the most remote and beautiful corners of the plateau and help protect and restore the landscape for future generations.

Ready to get to work? Learn about our projects

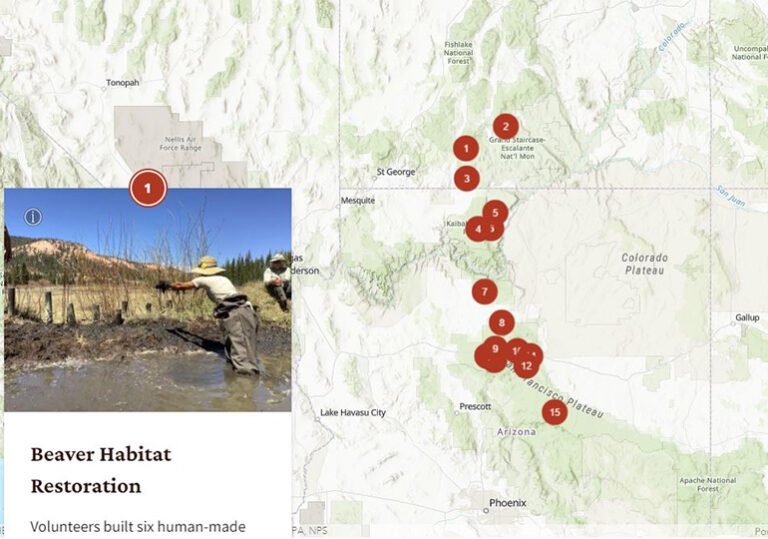

Springs

We work with volunteers to survey, restore, and monitor springs across the Colorado Plateau. Sometimes we build fences to protect fragile wetlands from the heavy feet of cattle; other times we pull weeds and plant native willows.

Streams

With work gloves and strong backs, volunteers move rocks, fix fences, and plant native species to help slow down the flow of water in streams. We return to our sites to monitor conditions and see our lasting impacts.

Pronghorn

Since 2006, Trust volunteers have helped make more than 25 miles of livestock fences passable for pronghorn in House Rock Valley. We replace the bottom strand with smooth wire and raise it 18 inches off the ground.

Native plants

Trust volunteers help native plants thrive. We pull weeds, build and fix fences, and plant native species to help degraded landscapes recover across the Colorado Plateau.

Kane Ranch garden

Volunteers help us nuture a small garden for native plants at the historic Kane Ranch in House Rock Valley. Volunteer stewards pull weeds and water the garden monthly.

Pinyon jay project

Volunteers are gathering information about pinyon jays to inform the sound management of forests across the Southwest. This is an independent project. Sign up today

Find out when volunteer trips open, and how to signup.

Volunteers in action

Together, we make a difference for the Colorado Plateau. See our accomplishments