Proposed Tusayan Development

Taking a close look at the proposed Tusayan development that threatens to guzzle up Grand Canyon’s waters

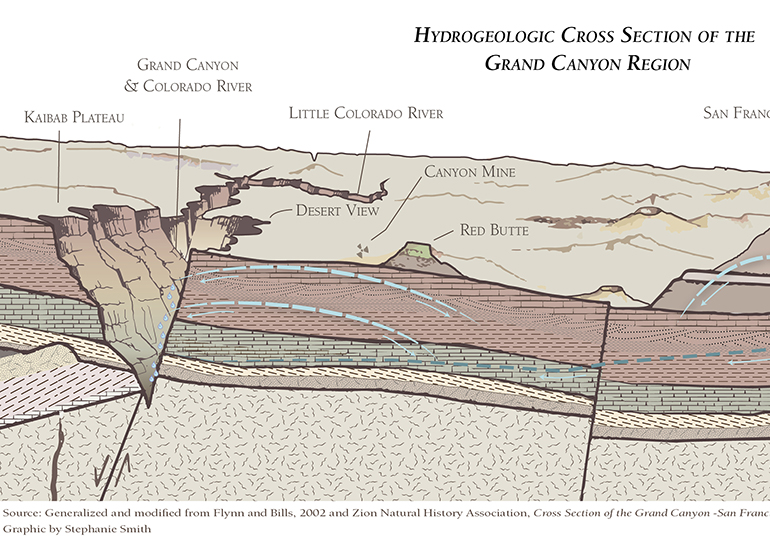

Water is scarce in the Grand Canyon region

For every proposed development near the Grand Canyon, we ask: Where will the water come from?

This question has sparked debate in the town of Tusayan, Arizona, where a developer wants to build a mega-resort on the doorstep of Grand Canyon National Park.

About the proposed Tusayan development

Hotels, shopping centers, a conference center, and more

The developer’s plan to build 2,500 hotel rooms, a convention center, possible dude ranch, and private residences would more than double the size of the town of Tusayan.

Thousands more faucets, tubs, and toilets would guzzle already scarce groundwater that feeds the Grand Canyon’s seeps and springs, strain existing infrastructure, and negatively impact the surrounding national forest and national park. We’re working to make sure that doesn’t happen.

Ask the Forest Service to take a closer look at the development

Where would the Tusayan development get its water?

The Stilo Development Group says it anticipates hauling water to its 1.8 million square feet of new commercial development.

The company has not disclosed the source of water or addressed the feasibility of running more than 45 tanker trucks roundtrip, every day, to satisfy peak season water demand.

Protect the Grand Canyon from a mega-resort. Ask the Forest Service to take a closer look at the proposal.

What’s at stake?

Plants, animals, and people of the Grand Canyon region. New developments like the one Stilo is proposing threaten to pump more water from an already shrinking supply of groundwater.

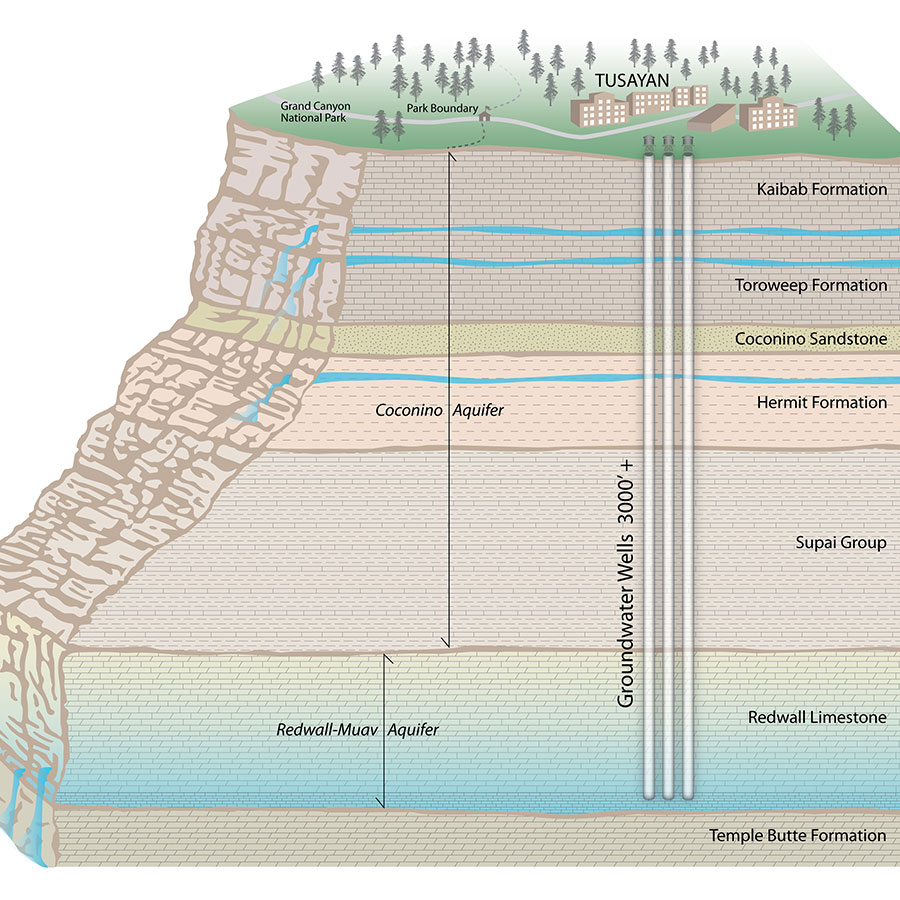

Where does Tusayan get its water?

All of Tusayan’s water comes from groundwater. Wells in Tusayan tap into the Redwall-Muav aquifer, which sits more than 3,000 feet beneath the surface. This aquifer is the primary source for the Grand Canyon’s seeps, springs, and streams.

Increased pumping would further deplete the already stressed aquifer. The National Park Service has documented long-term declines in flows of springs beneath the canyon’s south rim.

Tusayan development puts people, plants, and animals at risk

It’s not just willows, ferns, birds, and bighorn sheep that rely on Grand Canyon waters. The lifeway of the Havasupai people, whose sole source of drinking water comes from the Redwall-Muav aquifer, is also at risk. Current and future pumping of groundwater from the aquifer will cause irreparable harm to the tribe.

Read the Havasupai Tribe’s opposition to the Tusayan development (PDF)

The Forest Service needs to hear from you.

Tell them why you care about the Grand Canyon and ask them to take a closer look at the Tusayan development and protect the Grand Canyon’s precious waters.

Learn more about the Grand Canyon’s waters

Grand Canyon blog

Grand Canyon Conservation Support the Trust and protect the Grand Canyon

Your donation funds on-the-ground conservation efforts and advocacy work.