The hidden world of Grand Canyon caves and the researchers working to unravel the mysteries contained in strands of ancient bat DNA.

It’s a luminous October morning in the Grand Canyon. And, ironically for us, it’s a beautiful day to be outside. We’ve just rappelled 250 feet from the rim of the Redwall Limestone to reach an exposed alcove partway down the cliff’s face. This inconspicuous feature, hidden among a sea of vertical rock, is, in fact, not an alcove, but an entrance to a vast and complex cave system, older than the Grand Canyon and unlike anywhere else known to exist on Earth.

Inside, it is completely dark. We switch on our headlamps. I’m with expert cavers Shawn Thomas and Jason Ballensky, and we’re en route to continue survey and inventory efforts deep underground. Three additional teams are also heading to points unknown, all taking part in a collective effort to systematically map the cave. This small group of specialists are members of the Grand Canyon Cave Research Project, an organization with the goal of finding, studying, documenting, and preserving subterranean environments in the Grand Canyon region.

While many caves in the area contain signs of passage or use by Indigenous peoples, in this instance, perhaps because its entrances are located on vertical cliff faces, there is no discernible evidence that humans entered it prior to its modern discovery and exploration, which began in 2008.

More than 40 known miles of interconnected passageways

Since then, those investigating cave continue to add to a remarkable, ever-growing list of findings, including what are likely some of the oldest intact vertebrate remains ever discovered. All manner of small mammals, including ringtails, foxes, racoons, and wood rats, as well as thousands of desiccated bats so perfectly preserved that some — Townsend’s big-eared bats, silver-haired bats, hoary bats, and at least nine other documented species — are identifiable with a passing glance.

Throughout the cave’s more than 40 known miles of interconnected passageways, many of these deceased bats dangle from rare gypsum flowers, glass-like crystal formations that extrude from the walls and ceilings in such abundance that the spaces where they occur carry the aura of an otherworldly dimension.

“When I first looked at the bats, I was totally amazed”

It was in 2010 when Carol Chambers, professor of wildlife ecology at Northern Arizona University, first caught wind of a surprising find made during an ongoing cave inventory project in a remote part of the Grand Canyon — a huge cave filled with lots of dead animals, mainly bats.

Meanwhile, the inventory project continued to turn up incredible specimens of remains, many still with their skin and fur and so well preserved that it was difficult to distinguish them from live animals, begging the question, “How old are they?”

Chambers, already at work dating a single bat sample from a different cave, met with Shawn Thomas and former Grand Canyon National Park biologist Hattie Oswald, who presented her with photo documentation of 170 individual bats and their respective locations inside the giant cave.

“When I first looked at the bats, I was totally amazed,” Chambers said, during a recent interview.

She was instantly sold on helping to determine the bats’ ages, but it wasn’t until 2018 that the initial funds for radiocarbon dating were secured. With the wheels in motion, she spent hours reviewing Thomas’s and Oswald’s photos, agonizing over which bats to sample.

“I was trying to figure out what looks old,” she said, eventually deciding on nine bats representing five different species. “It turned out everything was old.”

The samples ranged in age from 3,700 to 31,000 years before present — shockingly ancient.

“I thought, holy smokes, we are really on to something here,” Chambers said.

The ages were astonishing, and only the tip of the iceberg. Needless to say, all were eager to date more of these exceptionally rare bat remains found throughout the cave.

How old are the bats?

After false starts in 2019 and 2020 due to wildfires and the coronavirus epidemic, Thomas returned to the cave in 2021 and collected samples from a different set of bats. Chambers sent them off to a well-regarded lab for dating. When her phone rang with the results, they asked her if she was sitting down.

The samples revealed ages beyond the limit of radiocarbon dating, which caps out around 50,000 years before present.

“I don’t know of anything else like it in the world. It just blows me away,” Chambers said. “There have been other bats radiocarbon dated that are quite old, but there’s nothing preserved like these individuals. Elsewhere, remains are mostly skeletonized, and nothing like what you see in this cave. It’s truly astonishing.”

How many bats are there in this Grand Canyon cave?

The cave contains hundreds to possibly thousands of undisturbed individual bats, all of which are in their original places. Their age range and the sample size are simply unheard of, and the research opportunities are just now unfolding. While Townsend’s big-eared bat is the dominant species, at least 11 other species of preserved bats have been found in the cave system.

“I’m interested in ancient DNA work,” Chambers said. “How have these species changed across time? Because we have such a large sample size, are we looking at the same kinds of genetics in these animals [today] as they were 50,000 years ago?”

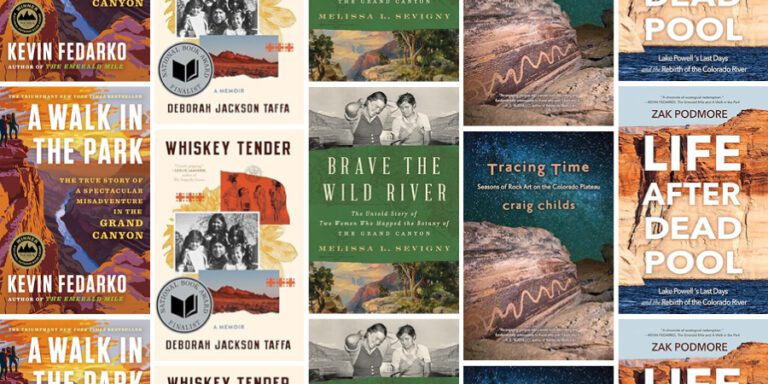

Read more:

Questions like this highlight the important role that caves play as habitat for wildlife and environments for preservation. Over the past 20 years or so, Jason Ballensky, who founded the Grand Canyon Cave Research Project, has located, mapped, and inventoried more caves than any other individual in the modern recorded history of the Grand Canyon, revealing countless wonders in the process. The most significant, of course, being the aforementioned “bat cave,” which now ranks as one of the world’s longest known caves. This documentation has opened doors for people like Shawn Thomas and Carol Chambers to make their own findings that contribute to a deeper understanding of the Grand Canyon and its natural history.

Rare preservation of soft tissue in Grand Canyon caves

Recently, I caught up with Vince Santucci, senior paleontologist with the U.S. National Park Service, to chat about the exciting news. Reiterating the significance of caves in the Grand Canyon and the rare opportunities they provide researchers, he said: “There are portions of the fossil record that are preserved within this cave that may not be preserved in any other environmental setting in the Grand Canyon, or anywhere else in the world. We tend to have the hard parts, the bones, the shells, things like that. We’re finding that there has been this rare preservation of soft tissue.

What is encountered in this particular cave is an anomaly. The value of being able to look at soft tissue preservation enables us to look at morphological characteristics: coloration of hair, size of ears, things that aren’t necessarily revealed when you look at bone. And then of course, the Carol Chambers component enables us this extremely rare opportunity to potentially look at ancient DNA.”

Impassioned, Santucci continued, “There is no other source of DNA known today, on planet Earth, of a large enough sample size that will enable us to look at those micro-genomic changes of a species over 50,000 years. This is revolutionary.”

Unchanged for at least 50,000 years

The remarkably stable conditions found throughout the entirety of the cave account for the animals’ remarkable state of preservation. Inside the cave, it is cool, arid, and well-ventilated with multiple entrances, and, of course, absolutely dark. The alignment of elements that enable this unique harmony to exist is truly special.

First, a big cave is needed to provide a stable environment. Then, a spread of more enigmatic factors must align to yield an internal temperature and relative humidity that can remain unchanged for at least 50,000 years. This calibration is distinct. Fifty thousand years is only a minimum age, a value established at the outer limits of radiocarbon dating. It’s possible that the environment inside the cave, including many of the deceased animals, has been in a state of preservation for far longer.

Amazingly, the cave continues to provide important habitat to bats to this day; the mammals have been seen flying in and out of the cave where their ancestors have roosted for tens of thousands of years.

So how old is this cave, exactly?

So how old is this cave, exactly? The current answer, like much of the canyon’s geology, is: It’s a complicated mystery. What is known about the cave’s origin and development — what scientists call its “speleogenesis” — extends into the realm of deep time, well before the Colorado River and its tributaries began carving through layers of rock to form the Grand Canyon we know today. What exists today as a cave was once part of an ancient aquifer that formed deep below an ancient water table. The aquifer, contained entirely inside the Redwall Limestone, was dissolving, saturated with acidic water until it was crosscut by developing Grand Canyon tributaries.

The system, essentially an intricate water tank, was sliced open by aggressive erosional forces occurring on the surface, causing fluids inside the cave to drain away completely.

Dating calcite formations in the cave’s former pool basins has provided researchers with enough data to establish a four million year timeline during which aridification took charge. It was during this extensive dry-out period that another anomaly occurred: profuse sulfate deposition. As moisture left the system, mineral deposits left behind as water evaporated — mainly gypsum — began forming crystals, crusts, needles, and other rare structures.

Today, breathtaking examples of these crystalline minerals are on display throughout much of the cave. Among them are gypsum flowers, a seldom-encountered formation extruding from the porous walls and ceilings of the cave like ribbons of glass. They occur in such dazzling numbers that those studying the cave are often left in a state of speechless disbelief.

These anomalies — the crystals, the perfectly preserved animals, the vastness of the cave, and the stable environment within — are exceedingly rare, only made possible through the harmonious alignment of so many nuanced factors.

The importance of caves as habitats

Shawn Thomas, who has been a key investigator since the surveying of this remarkable cave began in 2008, said, “My takeaway is that it highlights the importance of caves as habitats and as habitat anchors. This cave, and possibly others like it, is providing long-term habitat through climate change, not just for bats, but other wildlife as well. They might be some of the most stable environments to help support species through those changes.”

Like nowhere else on Earth

The Grand Canyon is like nowhere else on Earth, so maybe it shouldn’t come as a surprise that a cave like nowhere else would be found hiding within its endless web of canyons. It begs the question: What other kinds of places are yet to be realized in the Grand Canyon, and what can we learn from them? This cave is only one of an unknown number, and efforts to understand the mysteries found within have only just begun.

Caves undoubtedly play an integral role within the Grand Canyon landscape, and there are a huge variety of them. Many caves in the park are conduits for freshwater springs that nurture plants and animals and provide clean drinking water to Indigenous communities and park visitors. While these kinds of places are protected directly within the national park, the risk of pollution from uranium mining, among other activities taking place outside the park, requires direct action from all of us to ensure a healthy future for the Grand Canyon.

An outstanding example of this forward-thinking mentality was clearly demonstrated by the recently designated Baaj Nwaavjo I’tah Kukveni national monument. The monument ensures that 917,618 acres of forests and grasslands to the north and south of Grand Canyon National Park, including cultural and religious areas, plants, animals, and important water sources flowing into the Colorado River, are stewarded responsibly, including caves.

Only beginning to scratch the surface

In the words of Vince Santucci, “We… have only just begun to scratch the surface. Most of what is to be learned about the history of life on planet Earth is yet to be realized. It’s still out there, buried in caves and in badlands … how we manage and how we protect these resources in the Grand Canyon … is of the utmost importance.”

When Shawn, Jason, and I exit the cave, it is already dark outside. The sun, long gone beyond the western horizon, still casts a pale cerulean hue into the night sky. A gentle up-canyon breeze carries the scent of ozone and minty vegetation after an apparent fresh rain. We are surrounded by an atmosphere that feels particularly vibrant and dynamic, moving at light speed compared to the timeless realm inside the cave.

One by one, we ascend our rope leading back to familiar sights, sounds, smells, faces, and eventually cozy sleeping bags. Giant cliffs, as tall as ever, frame the heavens with precise, geometric lines. Orion beams overhead. Walking along the rim, I can’t help but feel like an interdimensional traveler, passing from one world and into another.

Stephen Eginoire is a photojournalist, writer, and designer based in southwest Colorado. Find more of his work at stepheneginoire.com

This story originally appeared in the fall 2024 issue of the Grand Canyon Trust’s Advocate Magazine.