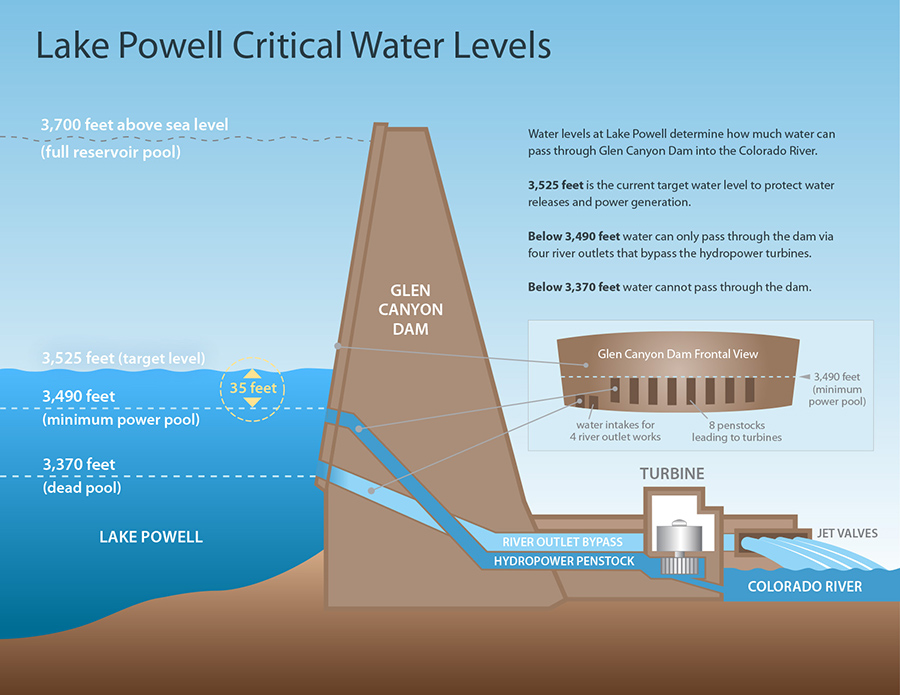

Glen Canyon Dam flooded over 180 miles of the Colorado River to form Lake Powell and provide power. How does the dam work?

The presence — or lack — of water has shaped the desert Southwest. Since the mid-1900s, dams and their resulting reservoirs have transformed this often-dry landscape.

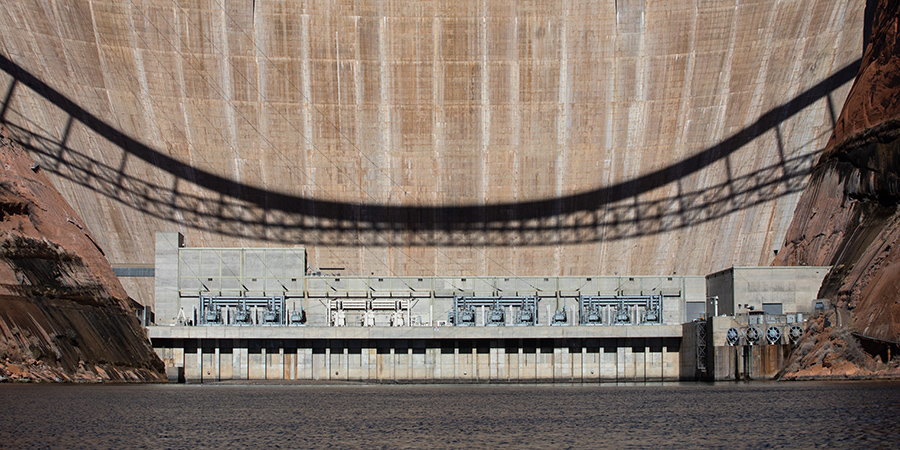

Near the border of Arizona and Utah, the 710-foot-tall Glen Canyon Dam flooded over 180 miles of the Colorado River in Glen Canyon to form Lake Powell. The lake is so massive that, although the dam shut its gates in 1963, it took until 1980 for Lake Powell to fill.

One of the primary uses of Glen Canyon Dam is water storage — ensuring that steady volumes of water can be sent downstream. The dam supplies water to farmers for agriculture. It also supplies cities like Phoenix, Los Angeles, and San Diego, and Native American tribes. And water flowing through the dam produces hydroelectric power.

The Colorado River Compact of 1922 governs how much water the states upstream of Glen Canyon Dam (Colorado, New Mexico, Utah, and Wyoming) and states downstream (Arizona, California, and Nevada) get, and how the Colorado River is managed. Beyond that, the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation is tasked with deciding how much water to move past Glen Canyon Dam and into the Colorado River through the Grand Canyon every year.

So, how does Glen Canyon Dam work?

Water collects in Lake Powell behind Glen Canyon Dam

Melting snow and monsoon rains flow across the high plateaus and red rock of the Upper Colorado River Basin and drain into Lake Powell. The 110,000-square-mile drainage includes the Colorado River from the north, the San Juan River from the east, and the Escalante River from the northwest, among others.

Lake Powell fills up

Lake Powell’s depth is measured as its elevation above sea level. When waters reach 3,700 feet above sea level, the reservoir is at “full pool.” Any more water would spill over the top of the dam. At this level, the twisting slot canyons of Glen Canyon are underwater, and you can drive a boat right up to Rainbow Bridge.

A series of wet winters in the early 1980s filled Lake Powell faster than water could be released downstream. Plywood boards were added to the top of the Glen Canyon Dam to buy a few more feet (and time). But over the last two decades of severe drought, lake levels have dipped, sometimes dangerously low.

Glen Canyon Dam generates power

At Lake Powell, 3,490 feet above sea level is called “minimum power pool.” That’s the lowest lake level at which the dam can produce power.

On the upstream face of Glen Canyon Dam, eight large tubes called “penstocks” allow water to pass through the dam into large turbines. The force of the water spins the turbines, generating electricity that powers air conditioners and lights up cities across the West. The penstocks also release water downstream into the Colorado River. More water flows through the dam 9-5 on weekdays to power businesses, and river runners in the Grand Canyon follow these flows.

In total, the Glen Canyon Powerplant churns out about 5 billion kilowatt hours of electricity every year. That’s enough to power nearly half a million U.S. households.

Water managers want to keep Lake Powell at or above 3,525 feet as a target elevation. That provides a 35-foot buffer above the minimum power pool elevation to both protect water releases downstream and ensure there’s enough water to spin the turbines that generate electricity.

River outlet works release water into the Colorado River

Below 3,490 feet above sea level (and above 3,370 feet), the only way to pass water through the dam is through four tunnels called “river outlet works.” The river outlets bypass the hydropower turbines. They spit water back into the Colorado River through jet valves below.

These bypass tubes are not regularly used. They’re primarily called into action during high-flow experiments so that larger amounts of water can be sent rapidly downstream. The river outlets, however, are only capable of releasing half as much water per second as can be released through the power plant. Therefore, as elevations drop, so does the ability to move water quickly through the dam.

Dead pool at Lake Powell

No, we’re not talking about a Marvel movie. If water in Lake Powell drops below dead pool — 3,370 feet above sea level — water can no longer move through the dam to the Colorado River below.

However, river flows are dynamic, and water will continue to flow into the reservoir from the Colorado River, Green River, San Juan River, and other tributaries. As water enters Lake Powell and the elevation rises above 3,370 feet sea level — even for just a moment — it’s no longer at dead pool and water will pass through the dam.

The future of Glen Canyon Dam

Dams produce power, store water for people to drink, nourish crops, and provide fun recreation opportunities like fishing, swimming, and kayaking. But they also prevent native desert fish from thriving, flood sacred places and awe-inspiring canyons, and drown cultural sites.

In 1992, the Grand Canyon Protection Act created a compromise to help minimize the adverse effects of Glen Canyon Dam and better protect the natural resources downstream. But drought is stressing an already overallocated river.

If the water level in Lake Powell drops below minimum power pool, operations of Glen Canyon Dam will be severely limited. This is leading some to advocate for doing away with the lake and bypassing Glen Canyon Dam completely.

Some 40 million people and 5 million acres of farmland rely on Colorado River water. With so many communities depending on it, we all must come together to forge a sustainable path forward for the Colorado River and all the life that relies on its flowing waters.