by Roger Clark, Grand Canyon Director

by Roger Clark, Grand Canyon Director

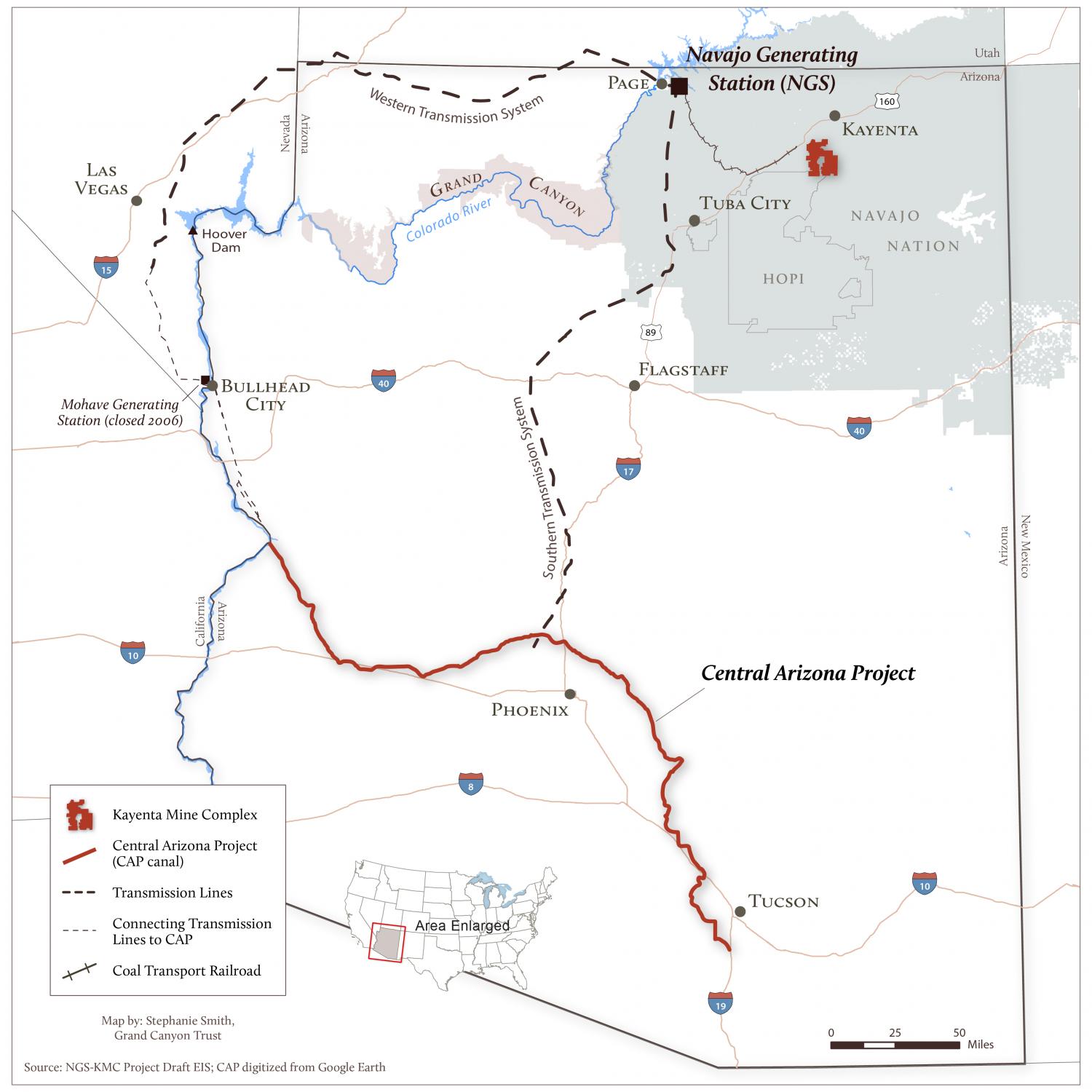

Navajo Generating Station’s 775-foot chimneys have been blackening Grand Canyon’s bright edges with coal smoke since 1974. Haze from the coal-fired power plant reduces visibility in Grand Canyon and Bryce national parks as well as nine other parks and wilderness areas across the Southwest. Nonetheless, the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation is proposing to renew expiring permits and leases to let the power plant keep running until 2044, burning coal shipped 80 miles by rail from the Kayenta Mine. We’re urging the Bureau of Reclamation to redo its environmental review, which shouldn’t simply aim to provide cheap power; it should also consider the need to protect the air, land, and water essential to sustaining our human environment.

Please take a moment during your holidays to protect the Grand Canyon from the West’s largest and dirtiest coal plant ›

The public is invited to weigh in by December 29, 2016.

The high price of cheap power

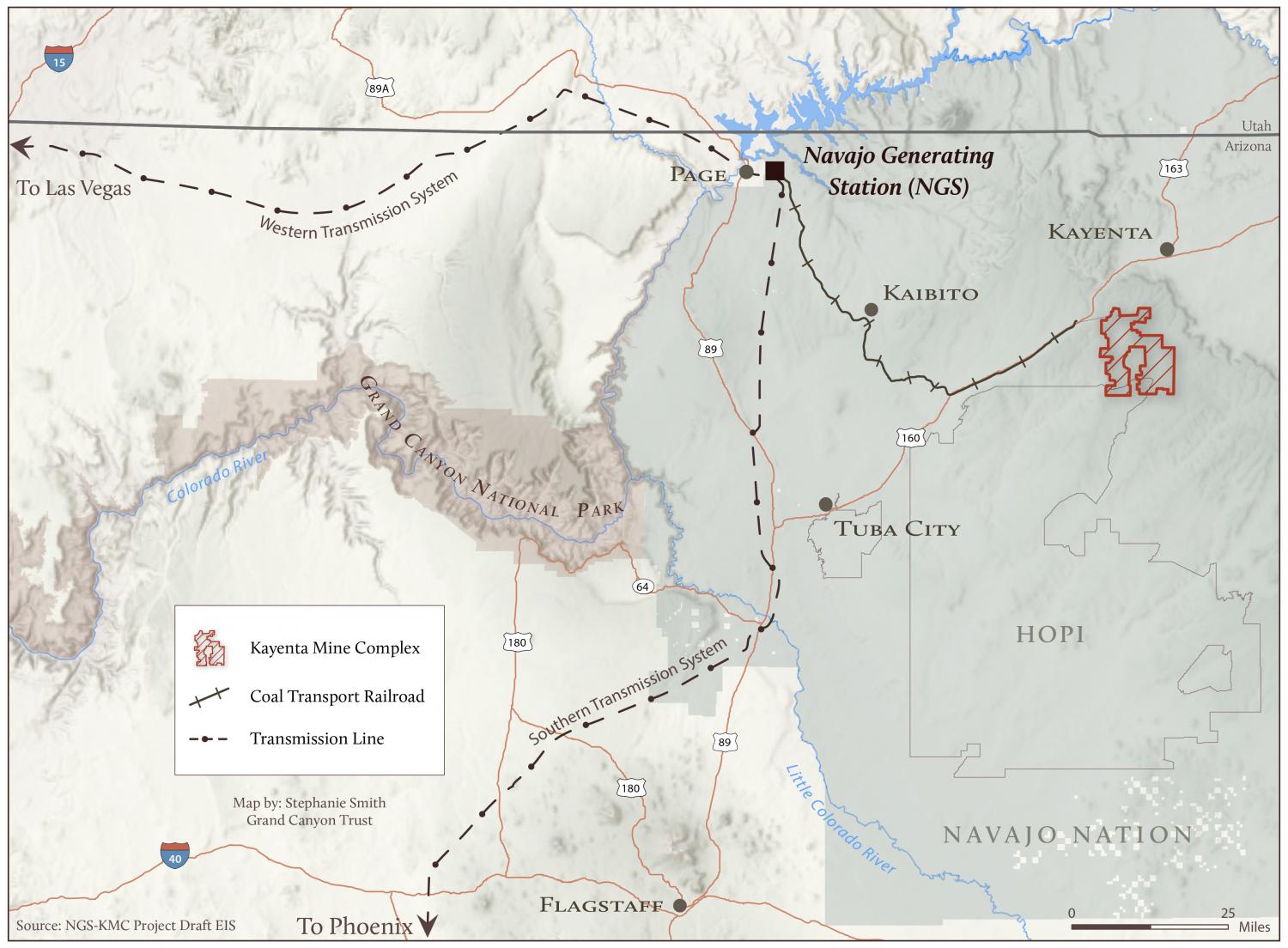

Navajo Generating Station, known locally as NGS, sits on land leased from the Navajo Nation, about 18 miles north of Grand Canyon National Park, near the town of Page, Arizona. For more than four decades, the plant’s boilers have been burning 2 million pounds of coal per hour to power three 750 megawatt generators.

NGS smokestacks have, for four decades, pumped more than half a billion tons of climate-changing gasses into the Earth’s atmosphere. Every year, they emit millions more tons of harmful pollutants into the surrounding air, land, and water. In a desert region that receives fewer than seven inches of precipitation annually, the plant’s steam and cooling systems consume enough water every year to sustain a city of 50,000 people.

Navajo Generating Station’s pollution plume impairs visibility at nearby parks and wilderness areas. Its mercury and other toxic emissions accumulate in surrounding ecosystems. People who live near the power plant are statistically more likely to suffer from respiratory disease.

Coal from Peabody Energy’s Kayenta Mine Complex, which also sits on land leased from the Navajo Nation and the Hopi Tribe, is hauled 80 miles by train from Black Mesa to NGS, whose furnaces devour over 30,000 pounds of coal per minute, 24 hours a day, 365 days a year.

Although royalties are paid to the Hopi and Navajo governments for coal from the Kayenta Mine, that revenue has come at a high cost. Before the ribbons were cut for the mine, thousands of residents were forced from their homes to clear the way for Peabody Energy to strip-mine nearly 100,000 acres of land, as permitted by the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs and the Office of Surface Mining. Remaining residents who live near the strip mines have been breathing coal dust for three generations. Many of their nearby wells and water sources have been damaged by coal mining. Ironically, many homes located near NGS and the coal mine that fuels it don’t have electricity; roughly 38 percent of households on the Navajo Nation lack power.

Where does all that electricity go?

The U. S. Department of the Interior receives 24.3 percent of the electricity generated by NGS. This power is used to run the 14 large pumps whose job is to lift more than 488 billion gallons of water uphill from the Colorado River through the 337-mile-long Central Arizona Project canal, owned by the Bureau of Reclamation. The rest of the electricity NGS generates goes to customers in Arizona, Nevada, and California.

Another 25 years?

To keep NGS and the mine that feeds it open for another 25 years, numerous federal leases and permits must be renewed beginning in 2019. The U.S. Bureau of Reclamation is contemplating renewing them through the end of 2044 and has issued an environmental review—called a draft environmental impact statement—that lays out several options, including replacing a small share of the power from NGS with renewable energy or natural gas, or letting NGS and Kayenta Mine close. But Reclamation’s analysis favors a “proposed action” that renews all necessary leases and permits to keep the mine complex operating and the generators running at NGS for 25 more years.

Minimizing harm to the human environment

The National Environmental Policy Act requires that a draft environmental impact statement fully disclose and assess the environmental, economic, and cultural consequences of the “proposed action” and alternatives to it, including the many impacts on the environment that have accumulated over past decades and that would result in the future, not only from NGS and the Kayenta Mine, but also from other activities in the region that cumulatively degrade its air, water, the public’s health, and the many other elements of this fragile desert landscape.

Specifically, the act requires federal agencies to identify and assess reasonable alternatives to proposed actions that will “avoid or minimize adverse effects of these actions upon the quality of the human environment.” In other words, to permit the continued operation of Navajo Generating Station and the Kayenta Mine Complex, federal agencies are required to “avoid or minimize” harm to air, land, and water essential to sustaining our human environment.

Our message to the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation

To comply with the National Environmental Policy Act, the Bureau of Reclamation must go back to the drawing board and revise the draft environmental impact statement it has prepared.

Here’s why:

- The proposed action—renewing the permits and leases—and the proposed alternatives fail “to avoid or minimize adverse effects” that the Navajo Generating Station and Kayenta Mine Complex have “upon the quality of the human environment.”

Reclamation should:

- Rewrite the draft environmental impact statement to have a purpose, through a long-term transition plan, of supplying: renewable energy, sustainable water supplies, and sustainable economic development, while minimizing negative impacts on Native American nations and those who currently benefit from NGS.

- Consider a reasonable rate increase for Central Arizona Project customers to better reflect true market values for water and cover some of the capital costs for constructing cleaner energy options. Central Arizona Project water rates are approximately one-tenth those of Las Vegas and other cities in the Southwest.

Urge the Bureau of Reclamation to redo its environmental review

ACTION ALERT: Send an email to the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation ›

More information:

- Read joint comments from the Grand Canyon Trust, Sierra Club, and Center for Biological Diversity submitted to the Bureau of Reclamation ›

- Read the Grand Canyon Trust and National Park Conservation Association’s joint comment letter to the Bureau of Reclamation ›

- Read the full draft environmental impact statement and review maps and other documents ›

- Download and print a comment form to submit by mail ›

Please mail your comments to: