The ongoing flooding problem at a uranium mine near the Grand Canyon continues.

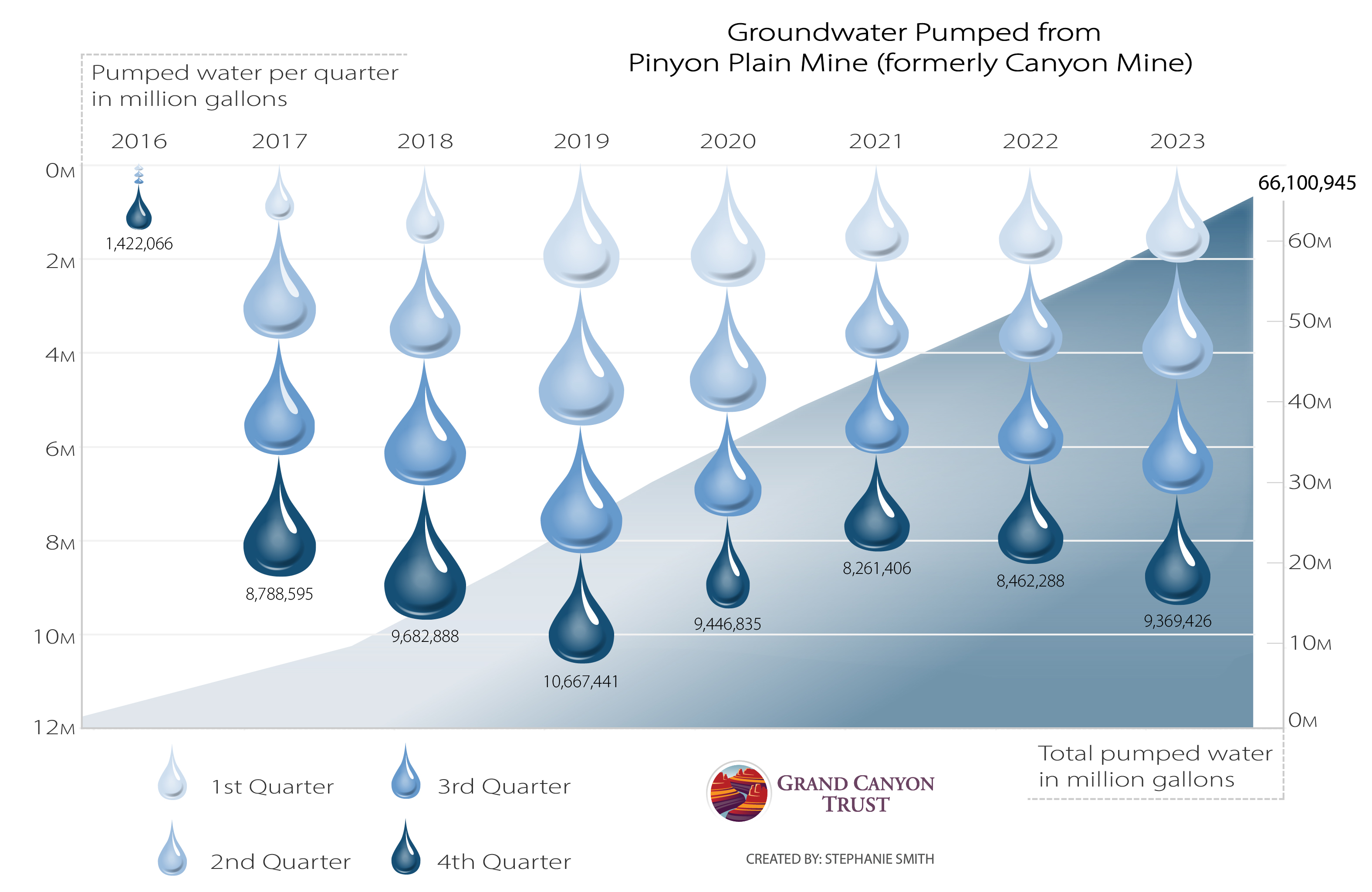

The ongoing flooding problem at Canyon uranium mine, near the Grand Canyon, continues, with over 9 million gallons pumped out of the mine shaft in 2023, bringing the grand total to over 66 million gallons — enough water to supply each resident of the nearby town of Tusayan for two years. That’s according to data submitted by the mine’s owner, Energy Fuels Resources, to Arizona regulators and recently published on the Arizona Department of Environmental Quality’s website.

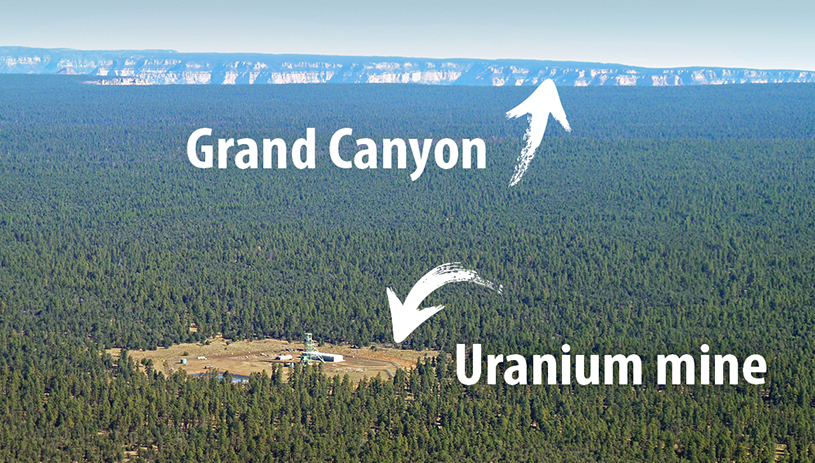

Where is Canyon Mine (aka Pinyon Plain Mine)?

Canyon Mine, renamed Pinyon Plain Mine, sits fewer than 10 miles from Grand Canyon National Park — well within the range that groundwater has been found to travel in the region — and inside the boundaries of Baaj Nwaavjo I’tah Kukveni – Ancestral Footprints of the Grand Canyon National Monument.

The mine, which is exempt from the monument’s mining ban thanks to the outdated 1872 General Mining Law and despite strong opposition from the Havasupai Tribe and many others, began extracting uranium ore in December 2023. The Havasupai Tribe has opposed the mine since before it opened in 1986 and considers the mine a threat to its drinking water and to its sacred mountain, Red Butte.

Radioactive uranium ore from Canyon Mine is expected to be trucked across the Navajo Nation to the White Mesa uranium mill, near the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe’s White Mesa community and a mile from Bears Ears National Monument, for processing later this year.

The Navajo Nation has banned all uranium mining and uranium transport on its land and recently reaffirmed its strong opposition to uranium hauling across Navajo lands, but the state of Arizona has not done the same for state highways that run through the Navajo Nation.

Mine punctures groundwater, flooding ensues

Canyon Mine pumped about 800,000 gallons of water out of its mine shaft between 2013 and 2015, but the mine’s water problems began in earnest in late 2016, when miners hit groundwater, puncturing a perched aquifer, and water began flooding into the mine shaft.

According to the mining company’s own data, that first year, in 2016, the company pumped over 1.4 million gallons of water out of the mine shaft. The next year, it was more than 8.7 million. And the problem has only continued. In 2018, the number was 9.6 million gallons, followed by another 10.6 million gallons in 2019. In 2023, more than 9.3 million gallons were pumped out of the mine shaft.

2016: 1.4 million gallons

2017: 8.7 million gallons

2018: 9.6 million gallons

2019: 10.6 million gallons

2020: 9.4 million gallons

2021: 8.2 million gallons

2022: 8.4 million gallons

2023: 9.3 million gallons

All told, more than 66 million gallons of precious Grand Canyon region groundwater have been pumped out of the mine shaft as of December 31, 2023. And water loss isn’t the only concern.

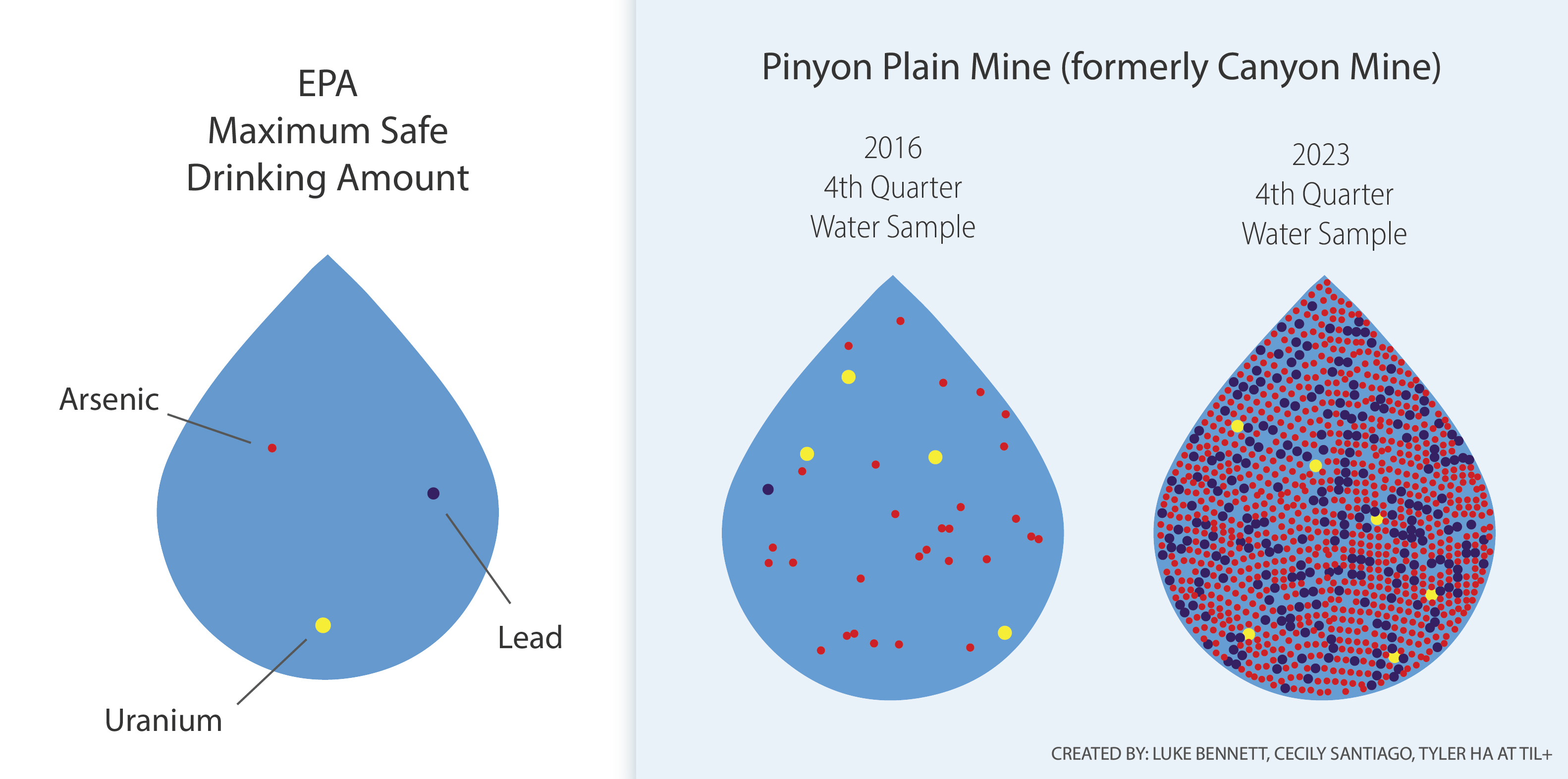

High levels of arsenic, uranium, and lead

Water pumped out of the mine shaft has shown high levels of heavy metals that could spell disaster if they ever leached into surrounding groundwater aquifers, including uranium, lead, and arsenic.

In the last quarter of 2023 (remember, the mine began extracting ore in December 2023), levels increased dramatically. Uranium levels reached six times the Environmental Protection Agency’s maximum contaminant level for safe drinking water. Lead reached 243 times the maximum contaminant level. And arsenic reached a whopping 812 times the maximum contaminant level.

At times, the mine’s owner has struggled to get rid of all this water. It pumps the floodwater into a large open-air pond inside the mine fence, where birds often alight to drink and bathe.

Visitors to the mine site have spotted burrows and tufts of fur caught in the chain-link where thirsty animals appear to have tunneled under the fence to reach the pond. On windy days, the misted water blows through the chain-link into the surrounding national monument lands.

Complex hydrogeology and water contamination fears

The mine sits above the Redwall-Muav Aquifer. The aquifer provides drinking water to Supai Village on the Havasupai Reservation at the bottom of Havasu Canyon, a side canyon off the Grand Canyon.

The Grand Canyon region is known for its fractured rock and complicated hydrogeology. Water flows downward, horizontally, and in multiple directions at once. To date, scientific research has not been able to determine how fast, how far, and by precisely what pathways water travels underground here. Many, and especially the Havasupai themselves, fear that the mine will contaminate water that the Havasupai Tribe depends on.

New science shows potential for uranium contamination

A Grand Canyon groundwater study pre-published in May 2024 found that data show the potential for contamination from the mine to reach springs on the south rim of Grand Canyon National Park and Havasu Springs near Supai Village, and advised that further tracer studies are needed to see how water flows. The study also called for additional monitoring wells at the mine to test for contaminant changes.

On February 20, 2024, Coconino County, where the mine is located, passed a resolution calling for the mine to close, and, at a minimum, for Arizona regulators to conduct robust and frequent air and water quality monitoring and release the results to the public monthly.

We likely won’t learn what the current 2024 flooding numbers at the mine look like until next year, but 66 million gallons are enough. And the more mineralized rock is exposed during mining operations, the greater long-term risk emerges that contaminated groundwater could find its way into surrounding aquifers, especially when the mine closes and the company is no longer present to manage the inflow of water. The mine is depleting precious groundwater and the risks to vital water sources, especially for the Havasupai Tribe, are poorly understood.

This is the wrong place for a uranium mine. It’s time to close and clean up Canyon Mine for good before the problem grows further.