What’s wrong with a uranium mine near the Grand Canyon? Number 1: It’s in the wrong place.

In May 2020, after a 7-year legal battle, a district court judge in Arizona helped clear the way for a mining company to dig radioactive uranium ore from a mine on national forest land not far from Grand Canyon National Park.

This was disappointing news given the poor environmental track record at the uranium mine in question — Canyon Mine — the vocal opposition of the Havasupai Tribe (whose leaders and citizens have opposed the mine for decades), and risks to vital groundwater.

There’s a long list of problems at Canyon Mine — I wrote a whole report about it — but here are a few of the top contenders:

1. It’s in the wrong place

Behind a chainlink fence in a meadow on the Kaibab National Forest, Canyon Mine is built on the ancestral lands of the Havasupai Tribe near Red Butte. Red Butte is a federally recognized traditional cultural property and the place where the Havasupai people believe they emerged into this world.

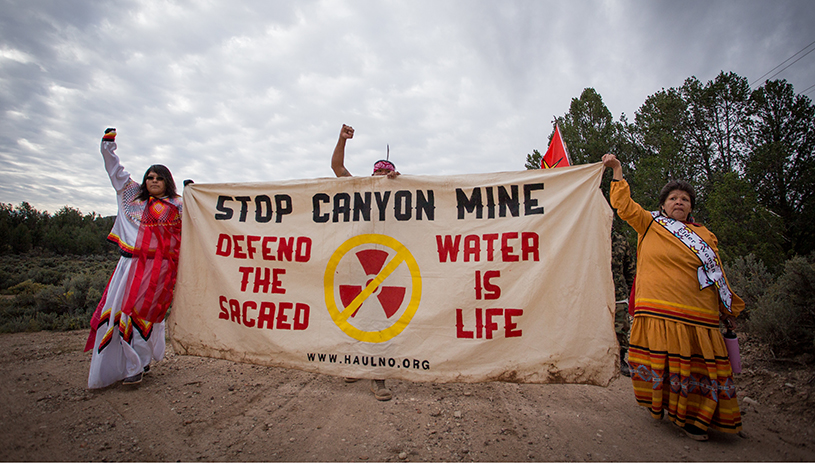

For years, the Havasupai Tribe has organized an intertribal gathering nearby where hundreds of Indigenous people from tribes across the region who have cultural ties to the Grand Canyon convene to demonstrate their opposition to the mine.

Oh, and those cliffs you see on the horizon in the photo? That’s just the Grand Canyon.

2. It’s a water fiasco

3. It’s attracting animals and birds

A mourning dove drinking and bathing in the evaporation pond at Canyon Mine. TAYLOR MCKINNON, CENTER FOR BIOLOGICAL DIVERSITY

The risk of contamination at Canyon Mine poses a danger to wildlife and concerns hunters and anglers. That’s why groups like the Arizona Wildlife Federation and Trout Unlimited support a permanent ban on uranium mining on public lands around the Grand Canyon.

Birds have been photographed drinking from the evaporation pond, where contaminated water from the mine shaft is pumped. The pond isn’t covered. And it’s often the only available surface water for miles, making it attractive to thirsty animals. This summer, Grand Canyon Trust staff observed large burrows and animal prints around the bottom of the chainlink fence, as well as tufts of fur that had caught on the fence, where animals appeared to have tunneled under, likely to get to water.

4. It’s not regulated strictly enough

The state agency charged with protecting Arizona’s clean water and clean air could be doing more to protect people, wildlife, water, and the environment from Canyon Mine. In the short term, the Arizona Department of Environmental Quality could require that the mine obtain a more stringent individual aquifer protection permit, rather than letting the mine owner squeak by with a more lenient general aquifer protection permit that we believe it’s not qualified to have. The state is currently deliberating over what kind of permit to require. The state could also require that the mine owner install a system of deep monitoring wells to keep tabs on any contamination that might be detected in the groundwater beneath the mine.

Canyon Mine isn’t the only uranium mine around the Grand Canyon. But it is a poster child for what can go wrong mining uranium in the Grand Canyon region. Meanwhile, there are over 800 active mining claims on public lands surrounding the canyon, waiting out a temporary ban on developing new mines that is set to expire in 2032 so long as no administration attempts to lift it sooner.

Taking stock of the potentially irreversible consequences of uranium contamination on water, the environment, and human health, Canyon Mine simply isn’t worth the risk.