Imagine 268 football fields stretching across a single mesa in southeastern Utah. Having a hard time? I don’t blame you. But that huge amount of space is what the operator of the White Mesa uranium mill hopes to eventually fill with toxic and radioactive sludge. The White Mesa Mill — a destination for toxic and radioactive wastes from sites across the United States — sits just a handful of miles north and up-gradient of the small Ute Mountain Ute tribal community of White Mesa.

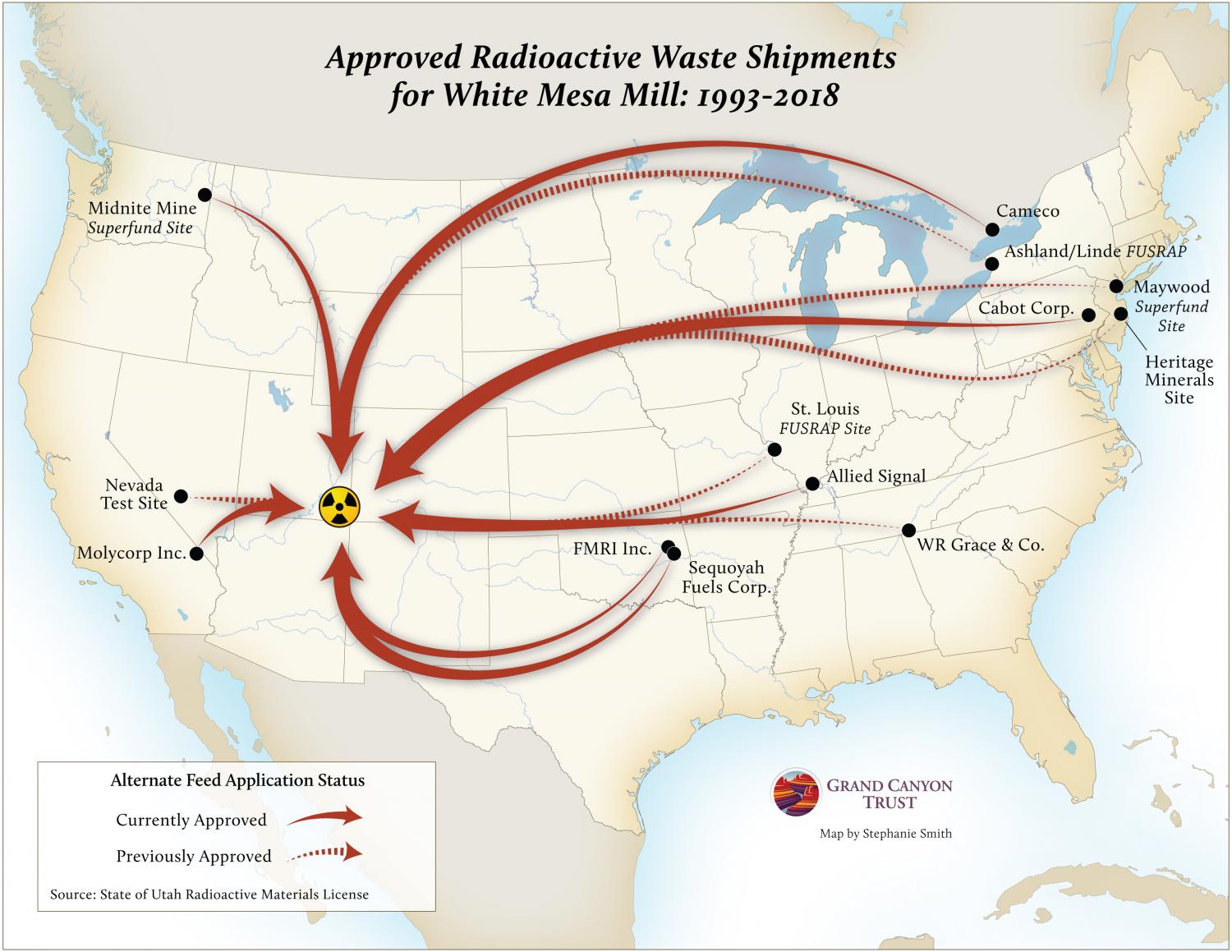

Today, over 200 of those radioactive football fields already exist at the mill, spanning roughly 275 acres. The mill operator wants to add 80 additional acres of waste ponds, stirring worries about whether the toxic goulash these ponds are meant to contain — a mix of chemical-laden wastes from the mill and the radioactive dregs of the Manhattan Project, rare-metals processing plants, and uranium mines, among other sources — could find a way into the groundwater that flows beneath the mill and toward the community of White Mesa, near Bears Ears National Monument.

Energy Fuels Resources Inc., the mill’s owner and operator, says there aren’t plans to build the additional 80 acres of waste ponds right away, but the company is still seeking authorization from Utah regulators to build them “to allow the Mill to respond to expected improvements in uranium market conditions.” The company may be referring to its hope that the Trump administration will grant the company’s request to impose import quotas on uranium. Those quotas would force nuclear utilities and anyone else buying uranium in the United States to purchase 25 percent of it from U.S. mines, whatever the cost. The basic premise behind that policy play is to line the pockets of companies mining and milling uranium in the U.S. by increasing your and my energy bills.

Uranium wastes don’t just go away

The company is planning for the mill’s future operations, but eventually, the mill will have to close. And closing up shop at a uranium mill is not like closing up shop at most any other business. The thing about uranium-mill waste is that it poses risks for all of eternity — and that’s not hyperbole. With a half-life of 4.5 billion years, uranium waste doesn’t go away. Making sure that the measures we put in place to protect our generation and our kids’ and grandkids’ generations is an expensive process, with costs in the tens or even hundreds of millions of dollars. And that process is fraught with uncertainties, from how much it will cost to secure the waste, to whether or not the ultimate closure process will truly withstand thousands of years of Mother Nature, especially in a changing climate.

More waste, higher stakes

And the more waste ponds, the higher the stakes — it’s more waste, more opportunity for an accident, and more area to eventually pay to secure and monitor.

The company’s application to the Utah Department of Waste Management and Radiation Control is over 1,300 pages long. It could take a while for the agency to review it, develop a proposed amendment to the company’s license to operate that would allow for the new waste ponds to be built, and open that amendment to public comment, but the Grand Canyon Trust will be ready when it does.

When the White Mesa Mill opened its doors in the 1980s, it was intended to operate for 15 years. Now, over thirty years later, the mill has left its toxic mark on the landscape and it’s time to start working on closing it down and cleaning it up, not on expanding it and making its impact worse.