Uranium Mining

Keeping uranium mining out of the Grand Canyon

You’d think the Grand Canyon — the homeland of at least 11 Native American tribes and one of the most visited national parks — would be protected from uranium contamination. Think again.

Uranium mines and mining claims outside park boundaries threaten to pollute the most remarkable gorge in the world.

We’re working alongside many partners in support of regional tribes to permanently protect lands and waters surrounding Grand Canyon National Park from mining.

Uranium deposits in the Grand Canyon

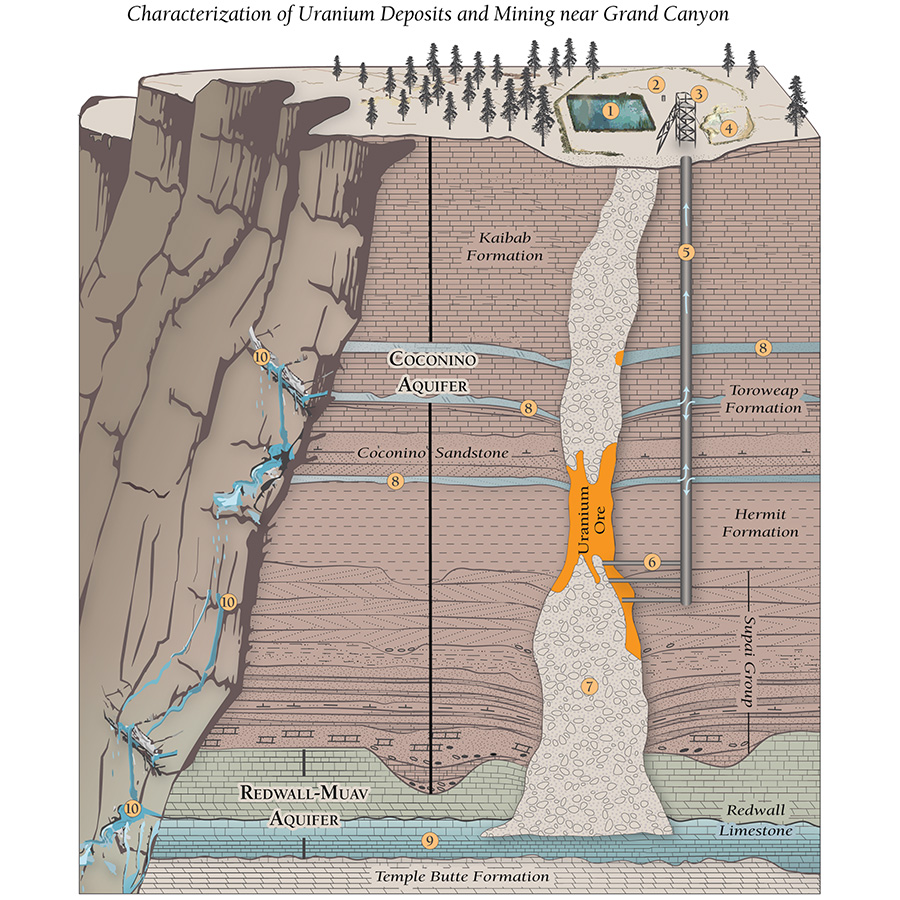

Uranium deposits sit deep within sandstone, siltstone, and mudstone layers across the Southwest. In the Grand Canyon region, uranium ore is found in geologic features called breccia pipes.

But there’s not very much uranium here, especially compared to the uranium-rich countries of Canada and Australia. Within the United States, the Grand Canyon region is home to a fraction — 0.2% — of our country’s uranium resources.

How much uranium is in the Grand Canyon?

No matter how you slice it, the Grand Canyon region simply isn’t sitting on the mother lode of U.S. uranium.

History of uranium mining in the Grand Canyon region

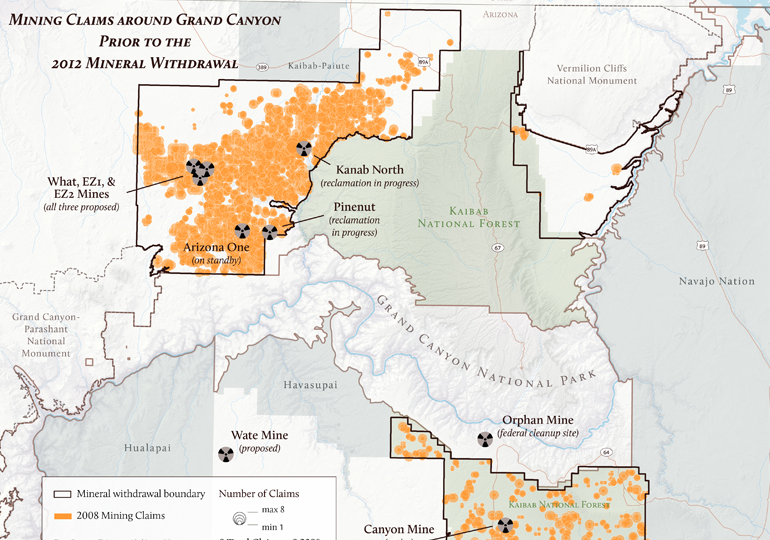

Uranium mining near Grand Canyon National Park began in the 1950s at Orphan Mine, just two miles from Grand Canyon Village. At least eight uranium mines have operated near the park, including the active Canyon Mine (renamed Pinyon Plain Mine) that threatens springs inside the Grand Canyon.

An active uranium mine less than 10 miles from Grand Canyon National Park

Canyon uranium mine (aka Pinyon Plain Mine) sits in a forested meadow in the Kaibab National Forest less than 10 miles from Grand Canyon National Park and on the Havasupai Tribe’s ancestral lands near its sacred mountain, Red Butte.

Few park visitors know a uranium mine operates on the doorstep of the Grand Canyon, risking the contamination of groundwater that feeds springs and seeps inside the park.

A uranium mine with a water problem near the Grand Canyon

Canyon Mine (aka Pinyon Plain Mine) is a poster child for what can go wrong at a uranium mine near the Grand Canyon. It’s been flooding since 2016, when miners hit groundwater.

More than 66 million gallons of precious Grand Canyon region groundwater have been pumped out of the mine shaft, and found to contain high levels of heavy metals like uranium, lead, and arsenic.

Uranium mining not worth the risks to Grand Canyon’s waters

Groundwater flow in the Grand Canyon region is complicated and not well understood.

Scientists are still trying to figure out where water flows and how quickly it gets there. The risk of contaminating the Grand Canyon’s waters is too high for the people, cultures, plants, animals, and economies that depend on them.

I oppose uranium mining near the Grand Canyon

Havasupai Tribe leads efforts to protect the Grand Canyon from uranium mining

The Havasupai live deep within the Grand Canyon and rely on a spring-fed creek to drink, cook, and irrigate fields of corn and alfalfa, as well as other ceremonial and cultural uses.

The tribe is worried that Canyon Mine (aka Pinyon Plain Mine) could contaminate groundwater that feeds the seeps and springs in their village. They have opposed uranium mining around the Grand Canyon since the 1980s.

“One of the arguments I recall was that, ‘Oh, you won’t see the contamination until hundreds of years from now…We’re not willing to take that risk. There’s only 757 of us left, and we just can’t risk that right now for the future of our children.”

FORMER Havasupai Tribal Council Member

Tribes win national monument protections

A coalition of 13 tribes successfully campaigned for Baaj Nwaavjo I’tah Kukveni – Ancestral Footprints of the Grand Canyon National Monument. The monument protects about 1 million acres of their ancestral homelands around Grand Canyon National Park. It also prevents new mining claims from being staked.

Mines with valid existing rights, including Canyon Mine, may move ahead inside the monument.

Uranium mining is not an economic driver

It’s the canyons, forests, and mountains — not uranium mines — that draw millions of visitors and their pocketbooks to the Grand Canyon state each year.

Find out how Grand Canyon National Park fuels Arizona’s economy

Low uranium prices kept Canyon Mine on standby for decades, but a market spike in 2023 spurred the mine into action.

Let the Environmental Protection Agency know that you oppose Canyon Mine

How Canyon Mine impacts tribes at every step of the process

Ore mined at Canyon Mine is transported about 300 miles through cities and towns in Arizona, the Navajo Nation, Hopi Reservation, and Utah, to the company’s White Mesa uranium mill for processing. See a map of the haul route

Uranium mining

Mining itself places the Havasupai Tribe’s water resources, traditional homelands, livelihoods, and culture at risk.

Uranium hauling

Uranium hauling transports radioactive ore across tribal lands and through communities that don’t want trucks passing through.

Uranium processing

Uranium processing at White Mesa Mill emits radioactive and toxic air pollutants into the neighboring tribal community.

When the price of uranium reached an all-time high, companies rushed to the Grand Canyon region. By the end of the decade, more than 8,000 mining claims surrounded Grand Canyon National Park.

Native communities, local governments, hunters, anglers, conservation groups, and many others successfully campaigned for a temporary mining ban around the Grand Canyon. The 20-year ban gave scientists time to better understand the risks of groundwater contamination.

President Biden designated Baaj Nwaavjo I'tah Kukveni – Ancestral Footprints of the Grand Canyon National Monument across nearly 1 million acres of tribes' ancestral homelands. The designation also includes a permanent ban on new mines around the Grand Canyon.

Uranium blog

Grand Canyon Conservation Support the Trust and protect the Grand Canyon

Your donation funds on-the-ground conservation efforts and advocacy work.