Stopping Grand Canyon Escalade

Supporting local families in their fight to stop the Grand Canyon tram

The confluence of the Colorado and Little Colorado rivers is sacred to the Navajo, Hopi, Zuni, and many Native peoples of the Grand Canyon region

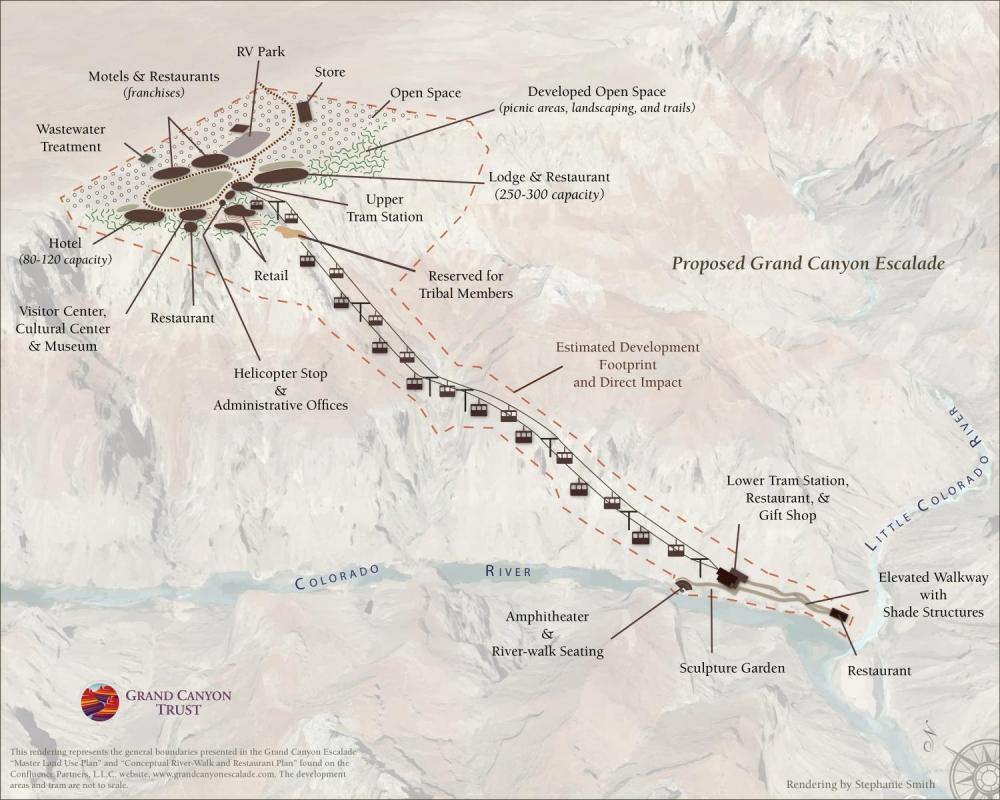

For nearly a decade, outside developers pushed the Navajo Nation to approve a mega-resort and tramway that would have carried 10,000 people a day to the bottom of the Grand Canyon. Tourists would have overrun this important cultural landscape.

After more than seven years of resistance from local families, the Navajo Nation Council slammed the door shut on the bill that would have paved the way for the so-called Escalade development.

Learn what the confluence means to Renae Yellowhorse

Save the Confluence families led opposition to Grand Canyon Escalade

Save the Confluence, a coalition of local Navajo families that have maintained homes near the confluence for generations, formed a grassroots group to stop the Escalade development. Over many years, they collected dozens of resolutions from Navajo Nation chapters, Native tribes and nations, and other groups, along with thousands of petition signatures against the development.

The Trust supports the Save the Confluence families

Join us to protect the Grand Canyon from destructive developments like Escalade.

The backstory

Navajo Nation slams door on Escalade

In 2009, Phoenix-based developers began pushing the Navajo Nation to approve the Grand Canyon Escalade, a mega-resort and tramway located on tribal lands on the east rim of the Grand Canyon. But a secretly negotiated master agreement included unfair terms and conditions that would have maximized profits for the developers. Read the summary or the full legislation.

Support for Escalade wavered. As politics in the nation shifted, the developers struggled to find a tribal council member to sponsor their legislation. When they finally did, and the bill worked its way through the Navajo Nation legislative process. The council ultimately slammed the door on Escalade by a vote of 16-2.

Many Native American tribes opposed the Escalade development

The Grand Canyon and confluence of the Colorado and Little Colorado Rivers are culturally significant to many tribes in the region.

The developer's proposed mega-resort and gondola tramway would be located on 420 acres of Navajo land (about 60 miles by car from Cameron, Arizona), at and above the confluence of the Colorado and Little Colorado rivers.

Over the next few years, developers worked behind closed doors to sketch renderings, find financial backers, and lobby the Navajo Nation to approve their project.

Then Navajo Nation President Ben Shelly and development partner Albert Hale signed a memorandum of understanding to move the Escalade project forward.

Negotiations continued among invited insiders.

A bill dropped before the Navajo Nation Council seeking $65 million in Navajo Nation funding for Escalade.

According to the Navajo Nation's legislative process, the bill had to then move through four committees before coming to a final vote, where a two-thirds majority was required for final passage.

The first of four committees voted against the Escalade bill in a 5-0 vote. The committee cited the following concerns: failure of the developers to get consenting signatures from local grazing permit holders, the $65 million investment required by the Navajo Nation Tribe, and the development's impact on sustaining the earth-based Navajo faith.

The Budget and Finance Committee voted against Escalade, with 3 opposed and 1 in favor of the bill.

Those opposed took issue with the lack of community involvement, opposition from local land users, and unanswered questions the developers have failed to address.

The final committee to debate the Escalade bill voted against it in a 14-2 vote. Committee members determined the required $65 million investment from the Navajo Nation could be better spent on improvements to communities, like roads, scholarships, and other infrastructure projects.

The bill now moved to the full council for deliberation and a final vote.

Without the votes to pass the Escalade legislation, the bill’s sponsor, Councilman Ben Bennett, put the legislation on hold, delaying the final vote. The next opportunity for the council to deliberate the bill would come in October, during the fall council session.

After several hours of debate, the Navajo Nation Council slammed the door on the Grand Canyon Escalade by a vote of 16–2.

The decisive vote was the culmination of seven gut-wrenching years of opposition by Save the Confluence families and Navajo citizens, who joined Hopi, Zuni, and Acoma leaders for the council's vote.

Fact sheets, maps, and more

Grand Canyon Trust blog

Get the latest Grand Canyon news

Grand Canyon Conservation Support the Trust and protect the Grand Canyon

Your donation funds on-the-ground conservation efforts and advocacy work.