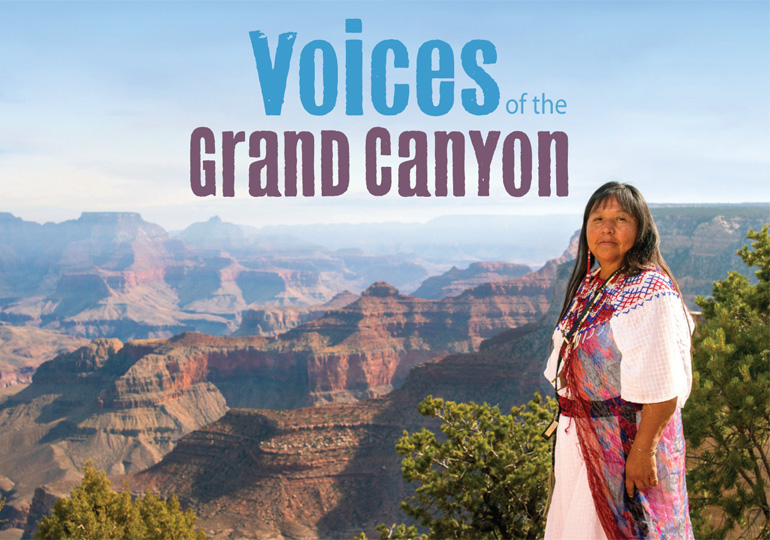

Before the Grand Canyon was a national park, it was the ancestral homeland of Native peoples. Hear voices of the Grand Canyon speak.

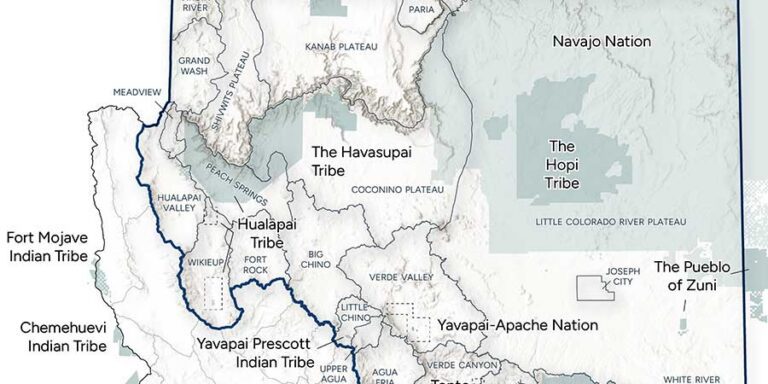

Experience the Grand Canyon alongside Jim Enote (Zuni), Nikki Cooley (Diné), Leigh Kuwanwisiwma (Hopi), Coleen Kaska, (Havasupai), and Loretta Jackson-Kelly (Hualapai) as they share what the Grand Canyon means to them and what they know in their hearts to be true.

Please accept statistics, marketing cookies to watch this video.

Director: Deidra Peaches

Featuring: Nikki Cooley, Jim Enote, Loretta Jackson-Kelly, Coleen Kaska, Leigh Kuwanwisiwma

This film was produced in collaboration with the Intertribal Centennial Conversations Group, which works to place Native voices at the forefront of education, stewardship, and economic opportunities in Grand Canyon National Park.