The Canyon Mine case shows how difficult it can be to stop a uranium mine on public land once it gets its foot in the door

After a decade-long legal effort to halt a uranium mine on national forest land not far from Grand Canyon National Park, a court ruling last week denied an appeal that could have shut the mine down for good. The case highlights how challenging it can be to stop a uranium mine on public land — even an unprofitable one — once it gets its foot in the door.

Canyon Mine (renamed Pinyon Plain Mine in an apparent attempt to distance it from its namesake, the Grand Canyon), sits on the Kaibab National Forest, in a meadow near Red Butte, a sacred site of great religious and cultural importance to the Havasupai Tribe.

Court decision greenlights uranium mine near the Grand Canyon

On February 22, 2022, a panel of judges in the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals in San Francisco ruled that the Forest Service was justified in ignoring the millions of dollars mining companies have sunk into developing the Canyon Mine when the agency determined that a uranium deposit mere miles from the bustling south rim of Grand Canyon National Park could be profitably mined.

This determination of profitability matters because uranium deposits on public lands are open to mining only if they can be mined and marketed at a profit. And if unprofitable, the mine’s claims could not be exempted under a temporary mining ban established in 2012 to protect the Grand Canyon region.

In the more than three decades since the Forest Service first greenlighted Canyon Mine in 1986, the mine’s owner has yet to produce a single pound of commercial uranium ore or earn a dime of profit from the mine. The Grand Canyon Trust and our partners have said it’s high time the mine close down and clean up before more damage is done, increasing the risk that the company won’t have the money to manage the mess.

The uranium industry has a track record of abandoning uranium mines and taxpayers are still paying for cleanup, including at the Orphan Mine inside Grand Canyon National Park, where an initial cleanup effort is estimated to have cost taxpayers $15 million. Nonetheless, the court ruled that the Forest Service could ignore the total past costs of developing Canyon Mine when weighing whether the uranium company could earn enough to make the enterprise profitable. An expectation of profit going forward, the court decided, was enough.

The long legal case against Canyon uranium mine

The Havasupai Tribe has opposed Canyon Mine since miners broke ground in the mid-1980s and remains deeply concerned about radioactive pollution from the mine. In the 1990s, uranium prices fell, and the uranium company stopped work. But when uranium prices briefly rebounded, the Forest Service decided that the mine was exempt from the 20-year ban on mining around the Grand Canyon put in place 2012, and that mining could move ahead under the 1986 plan. The Havasupai Tribe, along with the Trust and others, sued.

Last week’s decision is just the latest in a long series of appeals and challenges related to the case. Our attorneys are continuing to weigh legal options.

Water problems at Canyon Mine

The risks Canyon Mine poses to the Havasupai Tribe’s cultural identity, its water, and the environment surrounding the mine remain concerns. Workers at Canyon Mine pierced groundwater when digging the mine shaft in 2016, leading to serious flooding problems that have continued ever since. To date, more than 40 million gallons of water contaminated with arsenic and uranium have been pumped out of the mine shaft into an open-air evaporation pond, misted into the air, and hauled away by truck. The pond attracts birds and other wildlife.

Because the underlying rock is highly fractured, not just beneath Canyon Mine, but across the Grand Canyon region, scientists may never understand how far, how fast, and in what directions groundwater flows. Consequently, it’s unclear exactly where or when contaminated water from the mine could appear and that’s one reason why uranium mining has no place in such a culturally, ecologically, and economically important region.

Protecting the Grand Canyon from uranium mining

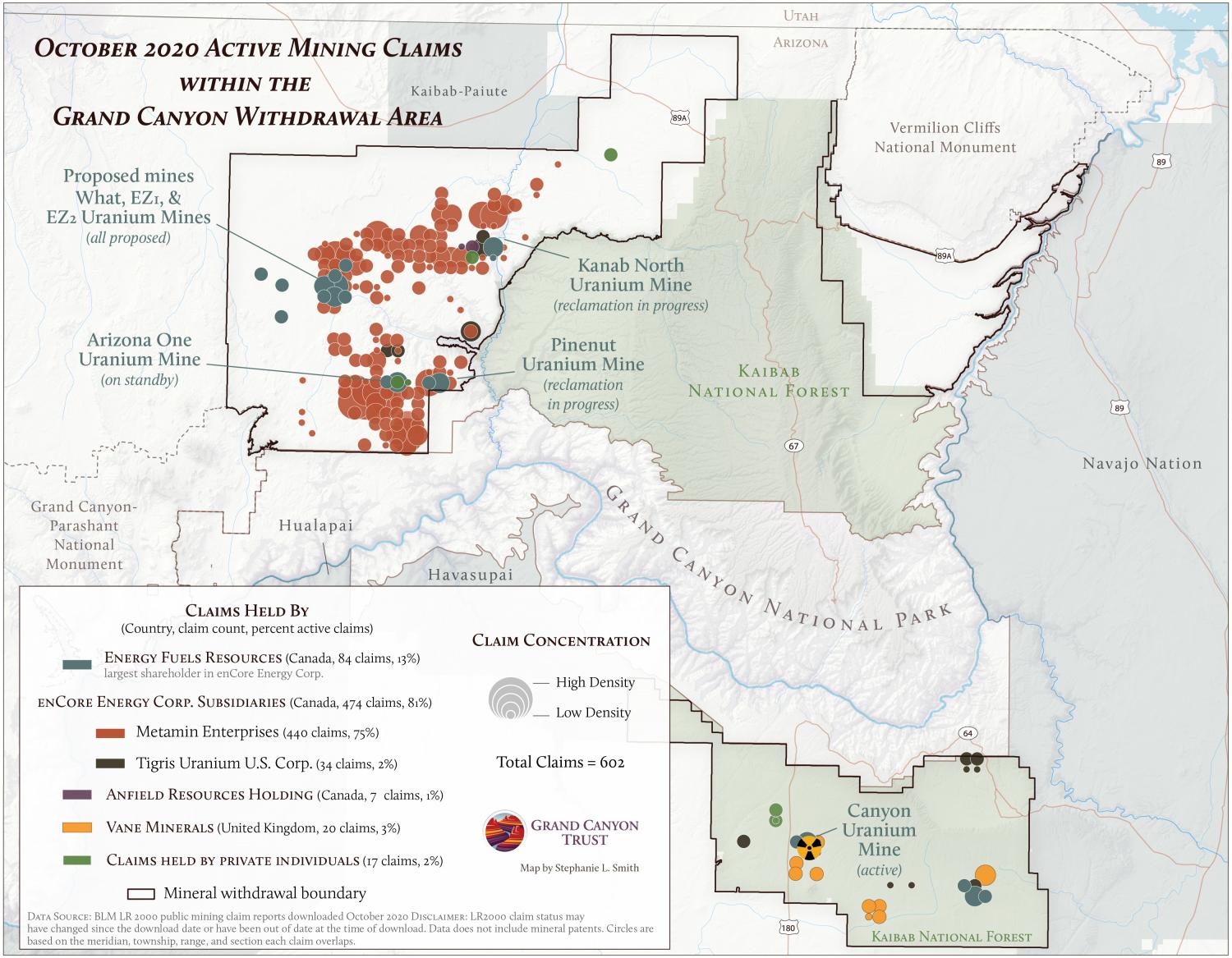

The years-long legal effort to halt Canyon Mine demonstrates how difficult it can be to stop a uranium mine once it gets its foot in the door, no matter how ill-conceived the mine might be. The temporary mining ban on public lands surrounding the Grand Canyon can’t stop mines that are exempted, but it can stop new mines. The ban, put in place in 2012, expires in 2032. There was significant pressure from the mining industry and its allies during the Trump administration to review and revise mining bans such as this one.

More than 600 active mining claims in the current mining ban area around the Grand Canyon are waiting it out one way or another. We need permanent protection for the Grand Canyon to stop these claims from being developed and new ones from being staked. We need the temporary mining ban to be made permanent.