Colorado National Monument is the eastern gateway to the canyon country of the Colorado Plateau.

It protects a land of red rock, deep chasms, and towering monoliths carved by water, wind, and time

Sample the park’s many hiking trails, or enjoy sweeping views from the scenic Rim Rock Drive. Either way, this rugged landscape will leave you thirsting for more. A system of mesas separates canyons with first names like Wedding, Monument, and No Thoroughfare, while rock monoliths called Kissing Couple and Liberty Cap hold their own. The playful names don’t come close to matching the fun you’ll have seeing the formations up close.

Visiting the monument

Millions of years ago, oceans (and later sand dunes) covered the Colorado Plateau. Eventually the seas receded, faults uplifted, rocks eroded, and Colorado National Monument became a showcase of the Chinle Formation, Wingate Sandstone, Kayenta, and Entrada layers that are laid bare today. Whether you choose to experience the monument by foot, bike, or car, you are in for a scenic treat.

Getting there: Driving east on I-70 towards Fruita, Colorado, take Exit 19 and turn south onto CO 340. Continue 3 miles to the west entrance of the park, crossing the Colorado River before veering right onto Rim Rock Drive. This road leads up into the park; after 4 miles you’ll come to the Saddlehorn Visitor Center and campground.

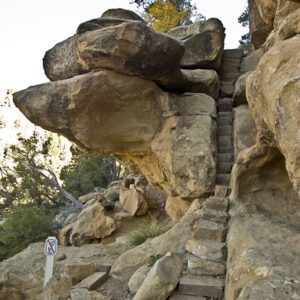

Colorado National Monument’s hiking trails are both challenging and rewarding, with lengths from 0.25 to 14 miles and elevation gains up to 1,100 feet. Bicycling the park’s Rim Rock Drive proves equally challenging. Whether bicycling or driving, you’ll find expansive panoramic views at 19 overlooks along this 23-mile route. The high, winding road, 2,000 feet above the Colorado River valley, looks west to the Book Cliffs and east to Grand Mesa, the largest flat-topped mountain in the world.

Fremont Indians hunted game, gathered plants, and farmed in this region until about A.D. 1250, followed by the Ute who also hunted and gathered in the canyons and on the mesas. In 1881, the U.S. government relocated the Ute to the Uintah-Ouray Reservation in eastern Utah.

Then in the early 1900s, a man named John Otto began advocating that the area now known as Colorado National Monument be given park status. He built trails so that everyone could see the geologic and scenic wonders that became a part of his spirit. But the features Otto fell in love with don’t look the same today. The sheer canyon walls and stately monoliths prove this landscape’s impermanence as they continue to erode, bringing new forms and altering the topography. Your photos may be the only unique record of this ever-changing landscape.

General Location Western Colorado

Closest Towns Grand Junction, Colorado

Cost Vehicle Permit: $25 (check the website below for current information)

Pets The general rule for pets is 'paws on pavement.' Pets may accompany their owners in the developed campground area and may be walked in the park along paved roads.

Managed By National Park Service

More Info NPS website

Adventure awaits

Sign up to get three hikes in your inbox every month for a year.

Special membership offer

Join the Grand Canyon Trust today to receive your adventure kit:

- $25 donation: a Grand Canyon map, The Advocate magazine subscription, bookmark, and sticker

- $75 donation: everything above plus four stunning note cards

- $100 donation: all the benefits of the $75 level, plus a Grand Canyon Trust hat

Related Hikes by Destination

Distance: 6.5 miles (10.5 km)

Difficulty: Moderate

Type: Loop hike

Distance: 2.2 miles (3.5 km)

Difficulty: Moderate

Type: Out and back

Distance: 2.4 miles (3.8 km)

Difficulty: Moderate

Type: Loop hike

State: Colorado

Nearest Town: Cortez, Colorado