by Amber Reimondo, Energy Director

A uranium mine near the Grand Canyon’s south rim with a flooding problem got the go-ahead to continue operating, though uranium ore has yet to be commercially mined at the site. In April, the state of Arizona granted a new groundwater permit to Canyon Mine, which threatens to contaminate seeps and springs in the Grand Canyon and the Havasupai Tribe’s sole source of drinking water. While the permit includes some improved requirements, no amount of precautions make the risk of permanent groundwater contamination near the Grand Canyon acceptable.

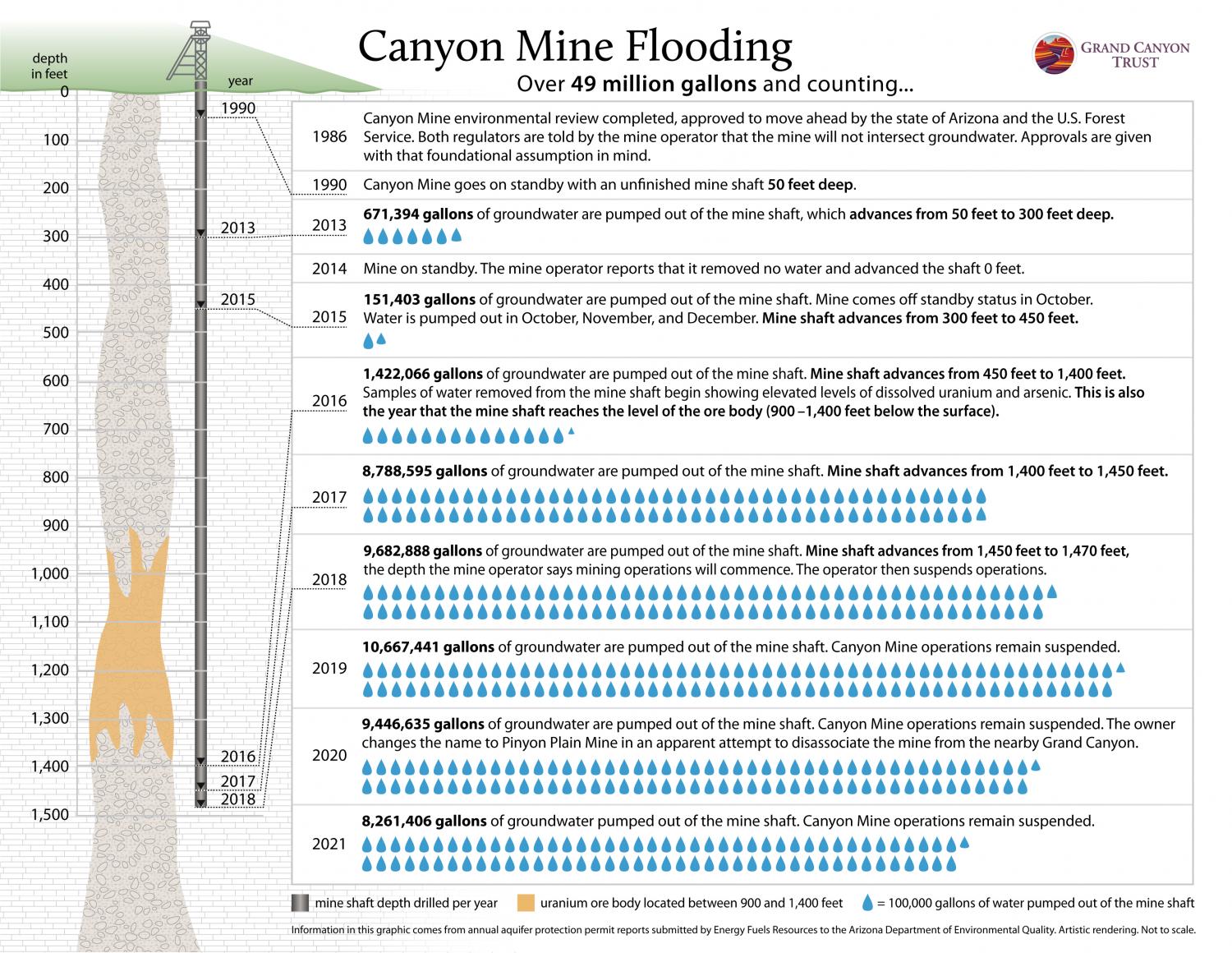

Since puncturing a shallow aquifer, Canyon Mine has taken on nearly 50 million gallons of groundwater and counting. The water infiltrating the mineshaft exceeds the EPA’s drinking water standards for uranium by as much as 300 percent and arsenic by as much as 2,900 percent. If the region’s mining history is any indication, those levels are sure to increase if and when the mine begins extracting uranium ore, worsening the risk that contaminated groundwater could eventually find its way beyond the mineshaft into increasingly limited and important groundwater resources.

Sometimes better still isn’t good enough

Aquifer protection permits are required for mines to operate. Facilities that have a good chance of polluting groundwater must get an individual aquifer protection permit.

In 2020, the Trust, the Havasupai Tribe, and our partners succeeded in convincing the state to stop issuing Canyon Mine general aquifer protection permits, which are less stringent, lack site-specific requirements, and include only voluntary and thus unenforceable standards.

In their decision to grant the individual permit, Arizona regulators thankfully included some improved measures as a result of public input. The agency will increase the mine’s post-closure monitoring to 30 years, add additional monitoring wells to the shallow aquifer (although still declines to require additional monitoring wells in the deeper regional aquifer), and require the mine operator to treat mineshaft water to decrease uranium and arsenic levels before it sprays the water on the mine site for dust suppression.

We’re glad that Arizona regulators have imposed additional standards in an attempt to reduce the risks of mining uranium from this landscape. But the new standards aren’t enough. Uranium contamination in the Grand Canyon’s complex underground plumbing system would be irreversible. Some risks just aren’t worth taking.

Too precious to risk

Uranium mining is risky business anywhere it’s done, particularly given that the half-life of uranium is measured in billions of years — a timespan longer than most people can comprehend. The radioactive metal is easily mobilized by exposure to oxygen. Once unearthed, it’s a challenge to prevent uranium from finding its way into the air we breathe and the water we drink.

This inherent risk is compounded near the Grand Canyon, where water is invaluable and the geology highly fractured, making groundwater systems complex and difficult to understand. Scientists have so much to learn about groundwater flow and pollution management — a monumental task to conduct comprehensive research in such a vast and remote region and on limited budgets.

In addition to threats of permanent contamination, flooding at Canyon Mine threatens to deplete groundwater sources in the midst of climate change. The mine operator’s plan for managing any contamination is simply to continuously pump groundwater.

Allowing Canyon Mine to continue operating in a critical and high-risk landscape, less than 10 miles from the south rim of the Grand Canyon and within a traditional cultural property for the Havasupai Tribe, is a gamble the Havasupai Tribe, the Grand Canyon Trust, and other nonprofit partners have urged regulators not to take.

What now?

The Trust and our partners will continue to support the Havasupai Tribe in its efforts to close and cleanup Canyon Mine, which is currently exempt from a temporary mining ban in the region put in place by the Obama administration. But the risk of uranium mining in the region doesn’t stop with Canyon Mine. Its flooding problem is a perfect example of why uranium mining doesn’t belong next to the Grand Canyon. And its sign-off from regulators and the courts shows just how difficult it is to stop a mine, no matter how ill-conceived, once it has its foot in the door.

That’s why the Trust, alongside a broad coalition of partners and community members, continues to push Congress to pass the Grand Canyon Protection Act. The bill would make the existing temporary mining ban permanent, forever safeguarding the region from the threat of uranium operations that are not, and will never be, safe for a watershed and a landscape as ecologically and culturally important as the Grand Canyon.

Urge your senators to support the Grand Canyon Protection Act and help it become law once and for all.