BY MARK UDALL

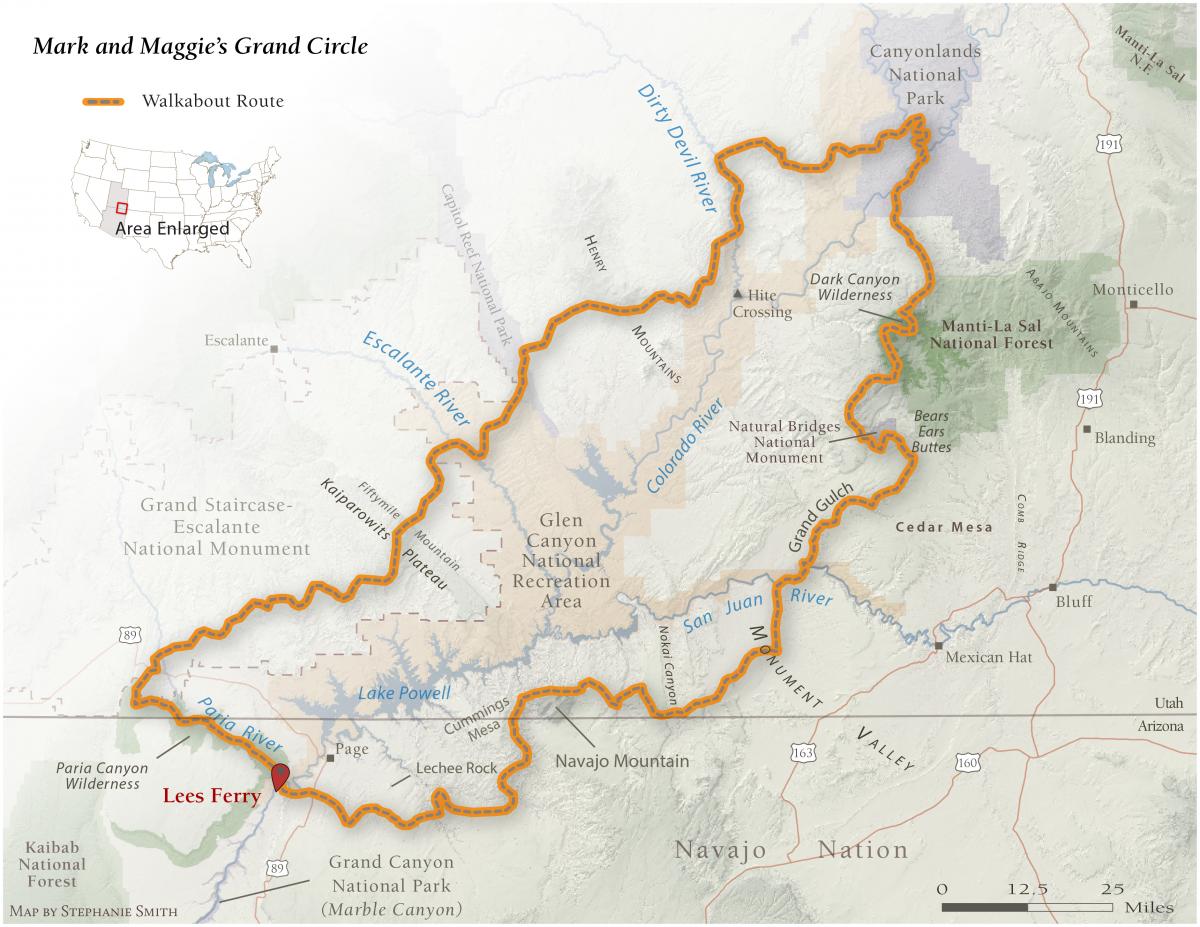

My wife Maggie and I paddled our pack raft from the historic gauging station on the east side of Lees Ferry to the boat ramp on the west. It was cloudy, cold, and windy, but we felt a quiet elation. We had just completed a 45-day, 400-mile walkabout from Upper Grand Gulch to Lees Ferry.

We’d started our initial walkabout in the early 1980s, traveling from Lees Ferry up the narrowing Paria, over the Kaiparowits Plateau down into the Escalante and circling the Henry Mountains. After 30 days and 300 miles, we stopped—temporarily—at Hite, at the top of Lake Powell. Three years later, we were back at Hite for a 300-mile traverse of the Dirty Devil and Maze Country, a swim across the Colorado River, and south to the natural bridges of White Canyon and cliff dwellings of Grand Gulch.

And now, 35 years, two children, and 16 years in Congress later, as we clambered out of our little raft at Lees Ferry, we’d completed our version of the Grand Circle in the most fascinating and mysterious landscape in the world.

I am a son of the Colorado Plateau. My father grew up on the Little Colorado and my mother in the high reaches of Rocky Mountain National Park. John D. Lee, Mormon explorer, founder of Lees Ferry and, yes, of Mountain Meadows Massacre notoriety, was my paternal great-great-grandfather. Jacob Hamblin, the Mormon leatherstocking and trusted friend of the Colorado Plateau’s Native American tribes, was my maternal great-great-grandfather. From an early age, I was captivated by the natural, geologic, and human history of the Southwest. And, as we walked day-to-day in the wildest, most remote terrain in the Lower 48, I keenly felt the presence of my own family’s history, and of the people who, for thousands of years, lived in and on these vast, arid lands.

Awe and respect for Mother Nature and for the scale and diversity of landforms: Navajo Mountain, Monument Valley, Lechee Rock, Nokai Canyon, Cummings Mesa. Intimacy and beauty in the turns of countless canyons, sculpture in every rock, the whisper of running water. The order and rhythm of life present in the flora and fauna from the intricate patterns of microbiotic soil, to maidenhair ferns hanging on a shaded wall, to the elusive but always present coyote. That order and rhythm ultimately depend on an element miraculous and scarce, both in the universe and on the Colorado Plateau: water.

Every morning, as we packed up our gear, we faced the question: Where is our next water? How much water must we carry? Having ample water in your pack is comforting and—at least initially— liberating, but those feelings come at a cost. More than two quarts on your back perversely becomes oppressive.

You face a conundrum: water’s weight slows you down and the more water you’re hauling, the heavier your attitude becomes. But not having enough is also a burden. On a long, hot traverse of Navajo Mountain with only a half-quart each, our mouths dried up along with our mental fortitude. We hoped, and managed to convince ourselves, that there would be water in Horse Canyon. Alas, Horse Canyon was dry. A hot evening wind blew as we crawled under a juniper tree, husbanded our water and ate “wet” food (tuna, dried fruit, candy). We endured a restless night of unsettled dreams hoping the spring on the next day’s map would be flowing.

Decades of desert travel have taught us some skills. Luck also plays a role. As it turned out, over half our nights we depended on potholes—pools of water found in natural rock cisterns of all shapes and sizes carved by wind and water over eons—where rainwater will sit for days, weeks, or even years. We were literally on our hands and knees praying to water, whether clear or colored red, brown, or green. Its smell, feel, our gratitude, our desire, even our unspoken fear of dry camps were all part of our daily existence. So it has always been for humans who live on the Colorado Plateau.

In all of our Southwest cultural traditions, there is a reverence for water. Every drop must be respected and cherished. When you must daily carry water, irrigate by hand, dig irrigation ditches, count on spring runoff and endure drought, you are mindful. Our technological prowess has allowed us to let that mindfulness slip. But science shows we have over-appropriated the waters of our river basins and strategic campaigns are underway to reduce, conserve, and reuse our finite water (See Robert Glennon’s article: “A Problem of Math”).

Now a greater existential challenge looms.

It affects all we hold dear on the Colorado Plateau. Listen to Hopi and Navajo sheepherders, ranchers, water engineers, and river runners. Like the Ancestral Puebloans, they see it and feel it.

Carbon emissions must be significantly reduced, and soon. Historically, we have always taxed pollutants like mercury and acid rain. Carbon dioxide, by this definition, is a pollutant, and it is my long-held view that we should apply a fee to carbon emissions. American innovation will then meet the challenge and new clean technologies will emerge. The recent Paris Agreement is a huge step by the international community. Regionally, we in the Southwest can lead in deploying wind, solar, and biomass energy systems.

I will be presumptuous and suggest that Maggie’s and my daily quest for water is a perfect metaphor for what our region faces.

As I savor and relive our walkabout, I desperately want to know that someday, my grandchildren will be able to retrace our route. I want them to know the Colorado Plateau on foot. If they can walk to water as we did, I have to believe our generation will have met the challenge of climate change. The residents of our modern southwestern communities don’t and can’t walk to water.

But if water is present in the tanks and potholes, hidden springs and crevices, and during the summer and winter monsoons as it has historically been, and as it was for Maggie and me, we will have kept faith with future generations.

But it will not be enough to hope, as we did on the flank of Navajo Mountain, that the Horse Canyons of the Colorado Plateau will hold water. It is up to us to act now.

Mark Udall represented Colorado in the U.S. Senate from 2009 to 2015 and in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1999 to 2009. He is a member of the Grand Canyon Trust's board of trustees.

Mark Udall represented Colorado in the U.S. Senate from 2009 to 2015 and in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1999 to 2009. He is a member of the Grand Canyon Trust's board of trustees.

EDITOR'S NOTE: The views expressed by Advocate contributors are solely their own and do not necessarily represent the views of the Grand Canyon Trust.